In this post, I’ll describe the use case and preliminary implementation of a new Yellowbrick feature that enables the user to print out colorized text that illustrates different parts-of-speech.

Part-of-speech tagging

Under the hood, the majority of NLP-based applications work in the same fundamental way; they take in text data as input, parse it into composite parts, compute upon those composites, and then recombine them to deliver a meaningful and tailored end result.

To transform a raw text corpus into data that can be used for modeling, there are five things that need to happen first: content extraction, paragraph blocking, sentence segmentation, word tokenization, and part-of-speech tagging. This means that part-of-speech tagging is a critical component in many natural language processing activities.

Once you have broken the documents down in to paragraphs, the paragraphs into sentences, and the sentences into tokens, you need to tag each token with the it’s appropriate part of speech.

Parts of speech (e.g. verbs, nouns, prepositions, adjectives) indicate how a word is functioning within the context of a sentence. In English as in many other languages, a single word can function in multiple ways, and we would like to be able to distinguish those uses (for example the words “ship” and “shop” can be either a verb, or a noun, depending on the context). Part-of-speech tagging lets us encode information not only about a word’s definition, but also its use in context.

If you’re using NLTK, the off-the-shelf part-of-speech tagger, pos_tag, uses the +PerceptronTagger()+ (which you can read more about here) and the Penn Treebank tagset (at least it does at the time of this writing).

The Penn Treebank tagset consists of 36 parts of speech, structural tags, and indicators of tense (+NN+ for singular nouns, +NNS+ for plural nouns, +JJ+ for adjectives, +RB+ for adverbs, +PRP+ for personal pronouns, etc.).

Hiccups

So I am working on a project at work that involves extracting keyphrases from unstructured text data, using an approach that is inspired by Burton DeWilde’s excellent post on the topic. As he explains:

A brute-force method might consider all words and/or phrases in a document as candidate keyphrases. However, given computational costs and the fact that not all words and phrases in a document are equally likely to convey its content, heuristics are typically used to identify a smaller subset of better candidates. Common heuristics include removing stop words and punctuation; filtering for words with certain parts of speech or, for multi-word phrases, certain POS patterns; and using external knowledge bases like WordNet or Wikipedia as a reference source of good/bad keyphrases.

For example, rather than taking all of the n-grams… we might limit ourselves to only noun phrases matching the POS pattern… that matches any number of adjectives followed by at least one noun that may be joined by a preposition to one other adjective(s)+noun(s) sequence…

This brute force strategy actually works quite well with grammatical English text. But what if the text you are dealing with is not grammatical, or is rife with spelling and punctuation errors? In these cases, your part-of-speech tagger could be completely failing to tag important tokens!

Or what if the text you are using does not encode the meaningful keyphrases according to the adjective-noun pattern? For example, there are numerous cases where the salient information could be captured not in the adjective phrases but instead in verbal or adverbial phrases, or in the proper nouns (as with named entity recognition). In this case, while your part-of-speech tagger may be working properly, if your keyphrase chunker looks something like…

grammar=r'KT: {(<JJ>* <NN.*>+ <IN>)? <JJ>* <NN.*>+}'

chunker = nltk.chunk.regexp.RegexpParser(grammar)

…you might indeed fail to capture the most critical verbal, adverbial, and entity phrases from your corpus!

Encountering these types of problems led me to think that it would be helpful to be able to visually explore the parts-of-speech in a text before proceeding on to normalization, vectorization, and modeling (or perhaps as a diagnostic tool for understanding disappointing modeling results). Discovering that a large percentage of your text is not being labeled (or is being mislabeled) by your part-of-speech tagger might lead you to train your own regular expression based tagger using your particular corpus. Alternatively, it might impact the way in which you chose to normalize your text (e.g. if there were many meaningful variations in the ways a certain root word was appearing, it might lead you to choose lemmatization over stemming, in spite of the increased computation time).

Existing tools

At first, I looked around to see if there was already something implemented that I could just pip install like a boss and move along. I didn’t find anything that was quite what I was looking for, though I did find a few interesting leads:

- “Add Colour to Text in Python” by Mark Williams

- Colorama, a cross-platform colored terminal text package on PyPI

- Clint, a module with tools for developing command line applications (including colored text).

- Stackoverflow question: “Print in terminal with colors using Python?”

- Termcolor, a little utility for ANSI color formatting for terminal output

One challenge that all of these resources address is the problem of dealing with ANSI colors, which can feel a bit limiting when you are spoiled by things like colorbrewer and the already-implemented-in-Python Matplotlib colormaps and Yellowbrick palettes. There are either 8 or 16 ANSI colors, depending on whether you count the “normal” and “bright” intensity variants. The colors are black, red, green, yellow, blue, magenta, cyan, and white.

However, the issue is that for the most part, all the resources I found treat colorization as akin to flipping a switch on or off using ANSI escape sequences. This works okay if the goal is to colorize blocks of text or other terminal output; the challenge is in adapting the switches for the within-sentence-level token colorization that is needed to illustrate parts-of-speech in a visual fashion.

The components of a part-of-speech colorizer

The goal is to enable visual part-of-speech tagging. In particular, I envisioned the PosTagVisualizer() as a simple utility that would let Yellowbrick users visualize the proportions of nouns, verbs, etc. and to use this information to make decisions about part-of-speech tagging, text normalization (e.g. stemming vs lemmatization), vectorization, and modeling.

We’ll need three main things:

- A dictionary that will map human-interpretable color names to ANSI formatted color codes.

- A dictionary that will map human-interpretable color names to the Penn Treebank tag set.

- A function that will connect (1) and (2) within a sentence that has already been tokenized and tagged.

Building a ANSI colormap

In order to build the ANSI colormap, I had to make some decisions about how much hard-coding to do in advance. One option is to reference the ANSI colors by their numeric codes, which basically correspond to the whole numbers between 30 and 39. If we do this, we will later need to prepend and append the appropriate escape sequences (e.g. the \033[0; or \033[1; prefix depending on color intensity, and \033[0m for the suffix). These codes need to wrap the specific text we mean to colorize. For instance

print("\033[0;31mi love chili peppers\033[0m")

… should print out

i love chili peppers

Ultimately, I decided to use Python string formatting brackets and hard code the rest into my colormap.

COLORS = {

'white' : "\033[0;37m{}\033[0m",

'yellow' : "\033[0;33m{}\033[0m",

'green' : "\033[0;32m{}\033[0m",

'blue' : "\033[0;34m{}\033[0m",

'cyan' : "\033[0;36m{}\033[0m",

'red' : "\033[0;31m{}\033[0m",

'magenta' : "\033[0;35m{}\033[0m",

'black' : "\033[0;30m{}\033[0m",

'darkwhite' : "\033[1;37m{}\033[0m",

'darkyellow' : "\033[1;33m{}\033[0m",

'darkgreen' : "\033[1;32m{}\033[0m",

'darkblue' : "\033[1;34m{}\033[0m",

'darkcyan' : "\033[1;36m{}\033[0m",

'darkred' : "\033[1;31m{}\033[0m",

'darkmagenta': "\033[1;35m{}\033[0m",

'darkblack' : "\033[1;30m{}\033[0m",

'off' : "\033[0;0m{}\033[0m"

}

Mapping the colors to Penn Treebank tags

The next step is to map the colors to the Penn Treebank tags. This was challenging mainly because there are a LOT of part-of-speech tags, and basically only 8 colors. If I was going to do this again, I might extend my options by using not only text colorization (e.g. foreground text coloring) but also text highlighting (e.g. background text coloring), just to give myself some more options for the colorization. What I’ve done for now is to group similar tags into color categories, so any kind of noun is green, whether it’s singular, plural, proper, or otherwise:

tag_map = {

'NN' : 'green',

'NNS' : 'green',

'NNP' : 'green',

'NNPS' : 'green',

'VB' : 'blue',

'VBD' : 'blue',

'VBG' : 'blue',

'VBN' : 'blue',

'VBP' : 'blue',

'VBZ' : 'blue',

'JJ' : 'red',

'JJR' : 'red',

'JJS' : 'red',

'RB' : 'cyan',

'RBR' : 'cyan',

'RBS' : 'cyan',

'IN' : 'darkwhite',

'POS' : 'darkyellow',

'PRP$' : 'magenta',

'PRP$' : 'magenta',

'DT' : 'black',

'CC' : 'black',

'CD' : 'black',

'WDT' : 'black',

'WP' : 'black',

'WP$' : 'black',

'WRB' : 'black',

'EX' : 'yellow',

'FW' : 'yellow',

'LS' : 'yellow',

'MD' : 'yellow',

'PDT' : 'yellow',

'RP' : 'yellow',

'SYM' : 'yellow',

'TO' : 'yellow',

}

Ultimately, this mapping could use some tuning, but in practice it was good enough to be able to visually detect some different parts of speech, so I proceeded.

A function to colorize the text

Now we need a way to retrieve the appropriate color code from our colormap and substitute in our token text into the string that the function returns:

def colored(text, color=None):

"""

Colorize text

"""

if os.getenv('ANSI_COLORS_DISABLED') is None:

if color is not None:

text = COLORS[color].format(text)

return text

Nothing too fancy here, but it works.

Now in the if-main statement

One of the decisions I made early on was that none of my package functions should perform any kind of tokenization or tagging. My reason for this was simple; the purpose of the package is not to actually perform the tokenization and part-of-speech tagging, it’s to visually evaluate the results of tokenization and pos-tagging. Also, since I ultimately wanted to be able to integrate this as a utility into Yellowbrick, I wanted to make sure that I would give as much control over things like data wrangling, normalization, standardization, vectorization, etc. over to the user as possible, which is pretty consistent with the API that we’ve conceived for the project. This will prevent us from having to add something like NLTK as a dependency for Yellowbrick.

For this reason, the word tokenization and part-of-speech tagging for my text happen inside the if-main statement, as do the requisite import statements:

import os

from nltk.corpus import wordnet as wn

from nltk import pos_tag, word_tokenize

text = """In a small saucepan, combine sugar

and eggs until well blended. Cook

over low heat, stirring constantly,

until mixture reaches 160° and coats

the back of a metal spoon. Remove

from the heat. Stir in chocolate and

vanilla until smooth. Cool to

lukewarm (90°), stirring occasionally.

In a small bowl, cream butter until

light and fluffy. Add cooled

chocolate mixture; beat on high speed

for 5 minutes or until light and

fluffy. In another large bowl, beat

cream until it begins to thicken. Add

confectioners' sugar; beat until stiff

peaks form. Fold into chocolate

mixture. Pour into crust. Chill for at

least 6 hours before serving. Garnish

with whipped cream and chocolate curls

if desired."""

# Tokenize the text

tokens = word_tokenize(text)

# Part of speech tag the text and map to Treebank-tagged colors

tagged = [

(tag_map.get(tag),token)

for token, tag in pos_tag(tokens)

]

print(' '.join(

(colored(token, color)

for color, token in tagged)))

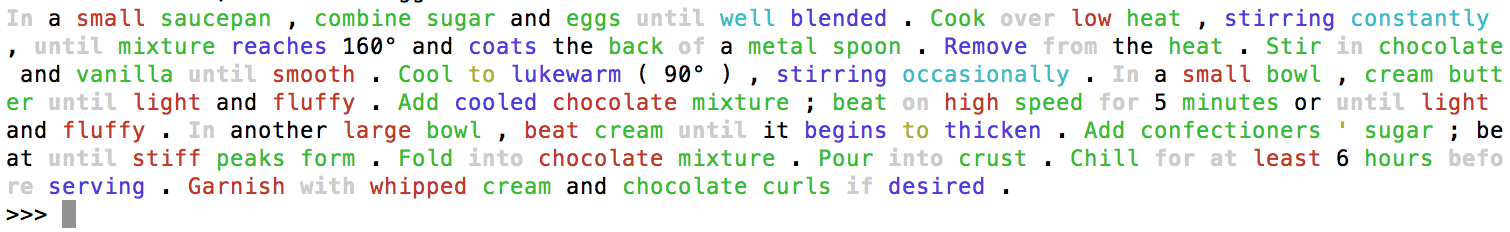

Here’s the result when I run that in my terminal:

It works! My next question was whether I could get it to work in a Jupyter Notebook, since the user tests and tutorials we’re adding to the Yellowbrick examples directory are in the form of .ipynb files.

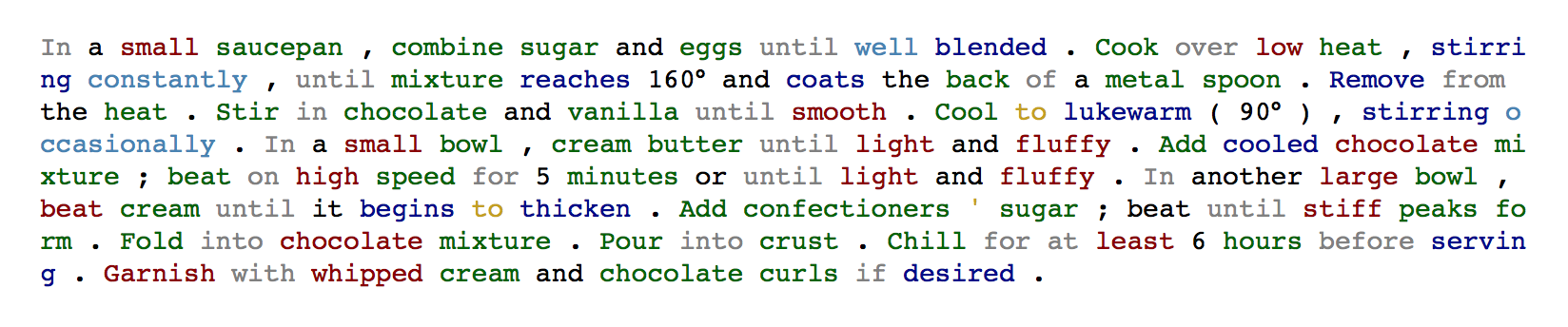

Here’s what it looks like when I run the code in a Jupyter notebook:

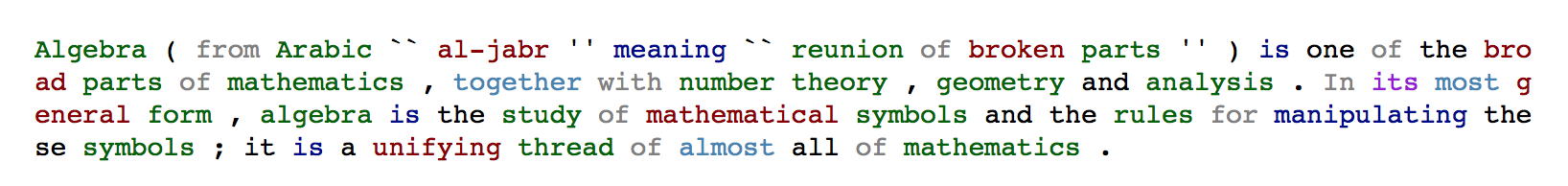

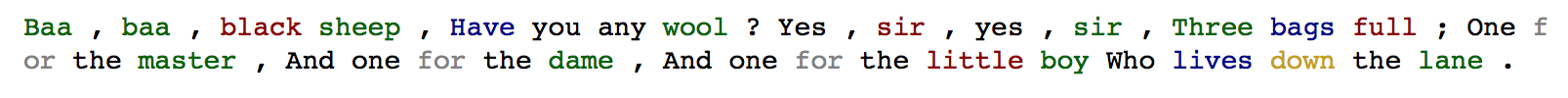

Now, just for comparison’s sake, here’s what a few other texts look like:

algebra = '''Algebra (from Arabic "al-jabr" meaning

"reunion of broken parts") is one of the

broad parts of mathematics, together with

number theory, geometry and analysis. In

its most general form, algebra is the study

of mathematical symbols and the rules for

manipulating these symbols; it is a unifying

thread of almost all of mathematics.'''

nursery_rhyme = '''Baa, baa, black sheep,

Have you any wool?

Yes, sir, yes, sir,

Three bags full;

One for the master,

And one for the dame,

And one for the little boy

Who lives down the lane.'''

Cool!

Conforming to the Yellowbrick API

Okay, so the next step is tricky. We need to decide what the best way is to integrate these little standalone functions into a class, and in particular, one that will conform to the existing Yellowbrick API, which has pre-defined methods like fit(), score(), draw(), transform(), finalize(), and poof(), depending on what type of Visualizer you have.

I was pretty sure that I wanted to subclass the TextVisualizer object, mainly because I imagined that the yellowbrick.text module would be the most natural place for people to look for visualization tools related to text data.

from yellowbrick.text.base import TextVisualizer

class PosTagVisualizer(TextVisualizer):

"""

A part-of-speech tag visualizer colorizes text to enable

the user to visualize the proportions of nouns, verbs, etc.

and to use this information to make decisions about token tagging,

text normalization (e.g. stemming vs lemmatization),

vectorization, and modeling.

Parameters

----------

kwargs : dict

Pass any additional keyword arguments to the super class.

cmap : dict

ANSII colormap

These parameters can be influenced later on in the visualization

process, but can and should be set as early as possible.

"""

def __init__(self, ax=None, **kwargs):

"""

Initializes the base frequency distributions with many

of the options required in order to make this

visualization work.

"""

super(PosTagVisualizer, self).__init__(ax=ax, **kwargs)

# TODO: hard-coding in the ANSI colormap for now.

# Can we let the user reset the colors here?

self.COLORS = {

'white' : "\033[0;37m{}\033[0m",

'yellow' : "\033[0;33m{}\033[0m",

'green' : "\033[0;32m{}\033[0m",

'blue' : "\033[0;34m{}\033[0m",

'cyan' : "\033[0;36m{}\033[0m",

'red' : "\033[0;31m{}\033[0m",

'magenta' : "\033[0;35m{}\033[0m",

'black' : "\033[0;30m{}\033[0m",

'darkwhite' : "\033[1;37m{}\033[0m",

'darkyellow' : "\033[1;33m{}\033[0m",

'darkgreen' : "\033[1;32m{}\033[0m",

'darkblue' : "\033[1;34m{}\033[0m",

'darkcyan' : "\033[1;36m{}\033[0m",

'darkred' : "\033[1;31m{}\033[0m",

'darkmagenta': "\033[1;35m{}\033[0m",

'darkblack' : "\033[1;30m{}\033[0m",

None : "\033[0;0m{}\033[0m"

}

self.TAGS = {

'NN' : 'green',

'NNS' : 'green',

'NNP' : 'green',

'NNPS' : 'green',

'VB' : 'blue',

'VBD' : 'blue',

'VBG' : 'blue',

'VBN' : 'blue',

'VBP' : 'blue',

'VBZ' : 'blue',

'JJ' : 'red',

'JJR' : 'red',

'JJS' : 'red',

'RB' : 'cyan',

'RBR' : 'cyan',

'RBS' : 'cyan',

'IN' : 'darkwhite',

'POS' : 'darkyellow',

'PRP$' : 'magenta',

'PRP$' : 'magenta',

'DT' : 'black',

'CC' : 'black',

'CD' : 'black',

'WDT' : 'black',

'WP' : 'black',

'WP$' : 'black',

'WRB' : 'black',

'EX' : 'yellow',

'FW' : 'yellow',

'LS' : 'yellow',

'MD' : 'yellow',

'PDT' : 'yellow',

'RP' : 'yellow',

'SYM' : 'yellow',

'TO' : 'yellow',

'None' : 'off'

}

def colorize(self, token, color):

"""

Colorize text

Parameters

----------

token : str

A str representation of

"""

return self.COLORS[color].format(token)

def transform(self, tagged_tuples):

"""

The transform method transforms the raw text input for the

part-of-speech tagging visualization. It requires that

documents be in the form of (tag, token) tuples.

Parameters

----------

tagged_token_tuples : list of tuples

A list of (tag, token) tuples

Text documents must be tokenized and tagged before passing to fit()

"""

self.tagged = [

(self.TAGS.get(tag),tok) for tok, tag in tagged_tuples

]

print(' '.join((self.colorize(token, color) for color, token in self.tagged)))

print('\n')

The main decision I had to make was the one to not implement a poof() method for the PosTagVisualizer. Under the hood, poof() calls finalize(), an internal method that creates a matplotlib plot object if the plot has not already been created. I decided that it would look weird to have an empty plot tacked on, so I made transform() do the bulk of the work in calling the colorize() method.

Conclusion

So, this works ok in the console and in a live Jupyter Notebook. I noticed that when I saved it as an .ipynb file and pushed to GitHub, it converted all the text to black and I lost the colorization. There are definitely something that I’d like to go back to tweak eventually.