In this series on multilingual models, we’ll construct a pipeline that leverages a transfer learning model to train a text classifier using text in one language, and then apply that trained model to predictions for text in another language. In this first post, we’ll look at the trajectory in expectations about data size over the last two decades, and talk about how that informs the model architecture for our text classifier.

The Rise of Small Data

Once upon a time, more data beat better algorithms. This was true because, no matter how bespoke your machine learning model, it could not scale complexity better than a model with a lot more information. The Netflix prize story taught us that spending time on feature engineering was more valuable than spending time on model architecture.

Companies eager to follow in the footsteps of Google and Amazon suddenly became very concerned with owning as much data as possible. This led us to the age of the data product, where focus began to shift towards building applications that would not only derive value from data, but also produce more data in return. Now not only was it true that more data was better than better algorithms, but also that more data was better than less data.

We find ourselves now in a technological landscape where many models have been trained on massive datasets, from Word2Vec to Watson to GPT-3. Published by Google in 2013, Word2Vec was trained on the Google news dataset which at the time consisted of about 3 billion words projected into 300-dimensional word vectors. Released around the same time, IBM’s Watson was purportedly trained on millions of documents, including dictionaries, encyclopedias and other reference materials. At the time, those datasets felt enormous, but our notion of what constitutes “big” in data is always changing. This past summer, OpenAI released their GPT-3, an autoregressive language model designed for natural language generation, and trained on 45TB of text.

Mega-Models with No Manners

And yet, there is some doubt about the results of these mega-models. Image recognition models that are trained on massive datasets containing mostly white, male faces unsurprisingly continue to have extremely high error rates when applied to portraits of brown-skinned women. GPT-3, touted as being the language model to end all language models, is trained largely on Western news stories and appears to suffer from deeply encoded Islamophobia.

Impressive and informed as they may be about the language used in news reporting, dictionaries, or on social media, mega-models are also constrained by the knowledge captured by their training corpora. As data scientists, we most commonly encounter these weaknesses when a model fails to correctly differentiate domain-specific documents. In a recent project, I realized that my model was erroneously conflating social media messages about the police with ones about studio art — both had a particularly high proportion of the word “canvas”.

There is also some question about how directly useful mega-models are in tasks that require the human capacity for understanding and adjusting to context. Human language, and how we use it, is very complex. Things like gesture, physical setting, and the relative ages of the conversants can have oversize impacts on the words we use. Local meanings and connotations often override dictionary definitions.

It would appear that more data alone is not the answer.

Cold Start Expectations

For the language tasks I work on, there are often two competing needs — the need for some degree of general language awareness as well as the need for a nuanced understanding of the specific context. The general awareness is important because it helps my models encode things like sentence structure or the concept of a hyponym. The contextual understanding is important because it allows my models to perform accurately and appropriately in situ, faced with highly domain-specific dialogue.

For such projects, I have historically used the data product approach, training the best model I can given the domain-specific corpus I have, however small. Generally this means deploying models that are initially a bit naive, but that have the capacity to improve as new data flows into the application. I have found this approach to be very effective once deployed in a production system.

However, I have also noticed that people’s thresholds for the model’s initial naivete are shrinking. Sometimes a low initial accuracy score is enough to stop a project in its tracks and shut the project down, even when it is presented in the context of a continuous learning system. We are, I think, entering a new phase of the data product revolution where the expectation is for cold-start (aka “zero-shot”), domain-aware models that are performant from the very beginning.

Delegated Literacy

In this series on multilingual modeling, we’re going to design a system capable of what I think of as “delegated literacy”. Our approach will combine a transfer learning model together with a small domain-specific dataset in the interest of producing a final bootstrapped model that is capable of balancing between general language awareness and context-specific language understanding.

The goal is to train a model able to detect criticism in book reviews in a number of different languages. Traditionally, this would require a massive labeled dataset containing book reviews and ratings in each of the desired languages for the application. Instead, we are going to “delegate” the general awareness portion, in this case, the capacity to understand multiple languages, to a transfer learning model.

NOTE: A transfer learning model is a deep learning model that has been pre-trained, usually on a very large dataset, and has encoded information from that original training dataset, but is still capable of learning via domain adaptation.

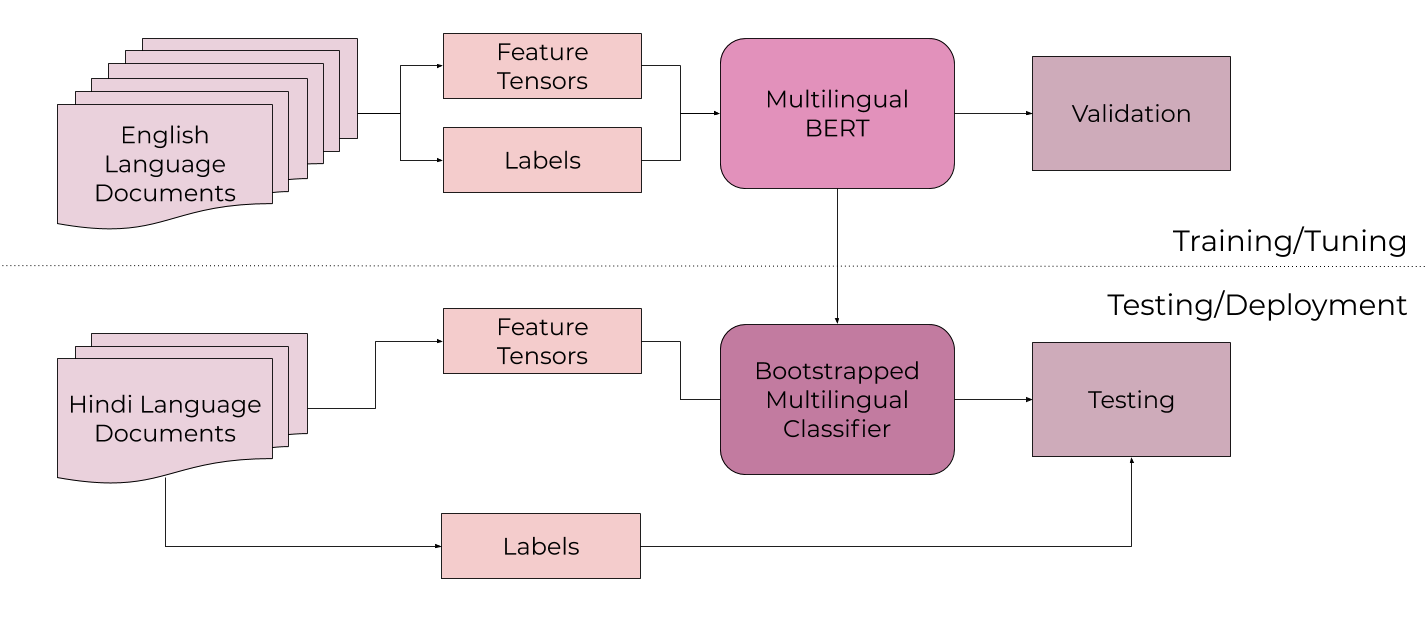

In the next post, we’ll dive into the general language awareness part of the pipeline using Multilingual BERT. We will then apply further supervised learning to this transfer learning model so that it is attuned to our specific corpus, in this case a labeled dataset of English-language book reviews. This additional training should attune the existing model to the notion of criticism in the context of book reviews. Finally, we’ll test the efficacy of our bootstrapped criticism-detection model by applying it to non-English book reviews, to assess whether the model is able to identify criticism in Hindi-language reviews.

References

- Tweet by Abubakar Abid on GPT-3 and Islam

- Anand Rajaraman, More data usually beats better algorithms

- Benjamin Bengfort, The Age of the Data Product

- Google, Word2Vec

- Joy Buolamwini and Timnet Gibru, Gender Shades: Intersectional Accuracy Disparities in Commercial Gender Classification

- Wikipedia, Watson