In this post, I’ll present a comparison of the experimental results of several published implementations of consensus methods for wide-area/geo replication. For each, I’ll attempt to capture which experiments were reported, what quorum sizes were used, and what the throughput and latency numbers were.

ePaxos

Iulian Moraru, David G. Andersen, and Michael Kaminsky. There is more consensus in egalitarian parliaments. In Proceedings of the Twenty-Fourth ACM Symposium on Operating Systems Principles, pages 358–372. ACM, 2013.

Abstract

This paper describes the design and implementation of Egalitarian Paxos (EPaxos), a new distributed consensus algorithm based on Paxos. EPaxos achieves three goals: (1) optimal commit latency in the wide-area when tolerating one and two failures, under realistic conditions; (2) uniform load balancing across all replicas (thus achieving high throughput); and (3) graceful performance degradation when replicas are slow or crash. Egalitarian Paxos is to our knowledge the first protocol to achieve the previously stated goals efficiently—that is, requiring only a simple majority of replicas to be nonfaulty, using a number of messages linear in the number of replicas to choose a command, and committing commands after just one communication round (one round trip) in the common case or after at most two rounds in any case. We prove Egalitarian Paxos’s properties theoretically and demonstrate its advantages empirically through an implementation running on Amazon EC2.

Leadership Style

There is no designated leader, and there are no leader elections. Each command gets a new leader. Multiple replicas can act as leader simultaneously for different commands.

Experiments

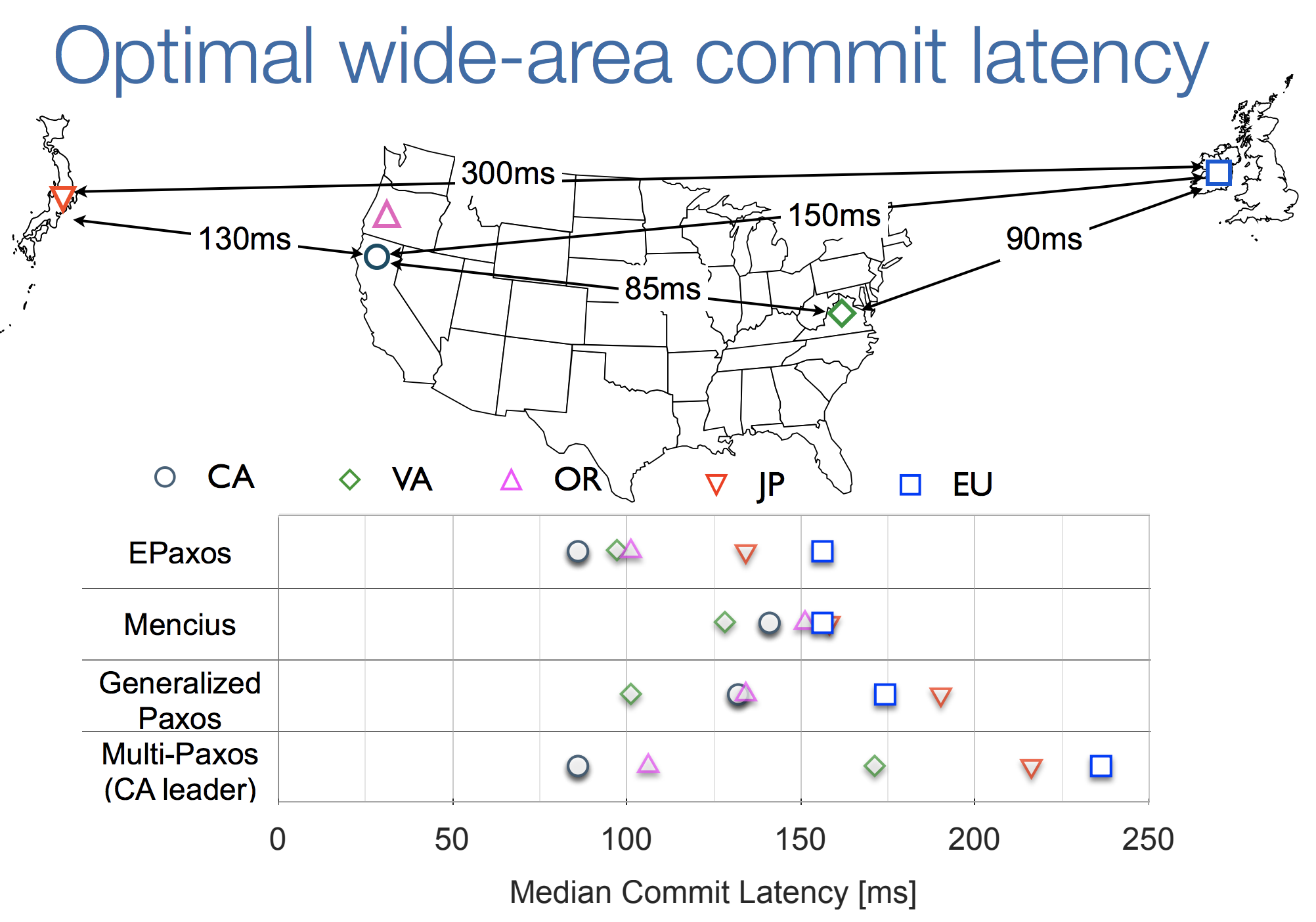

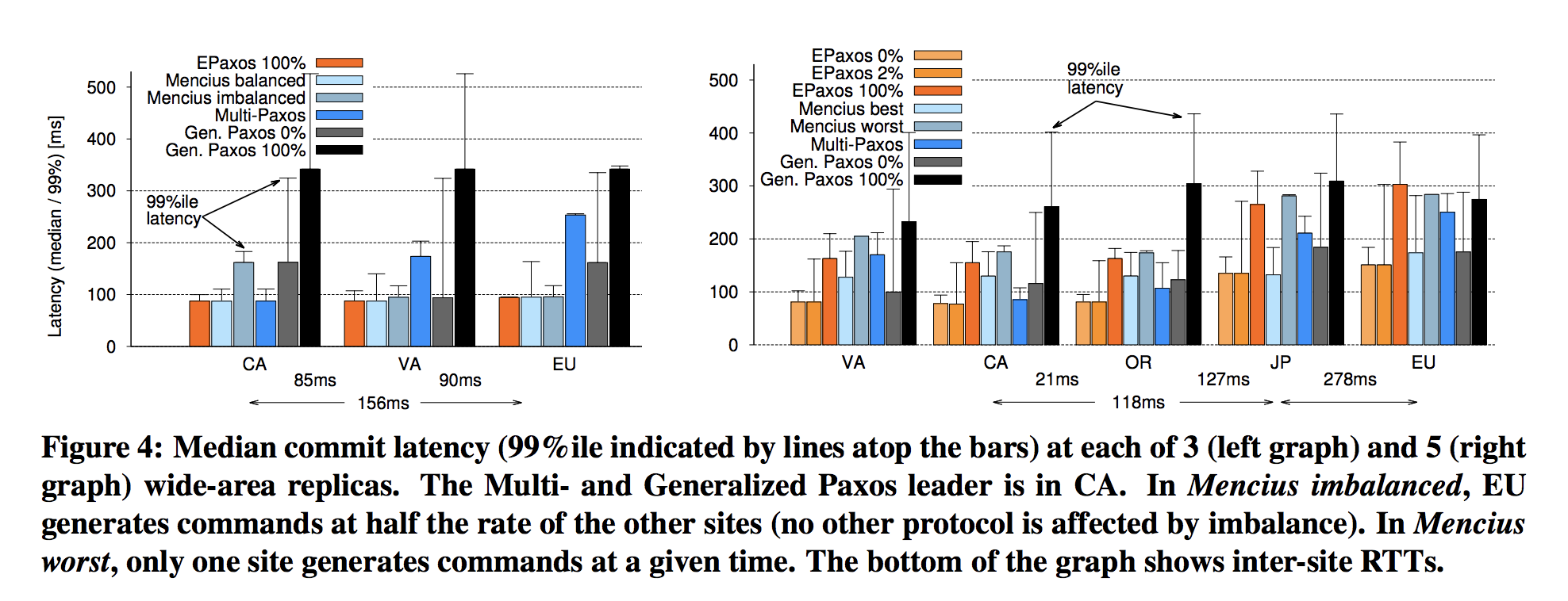

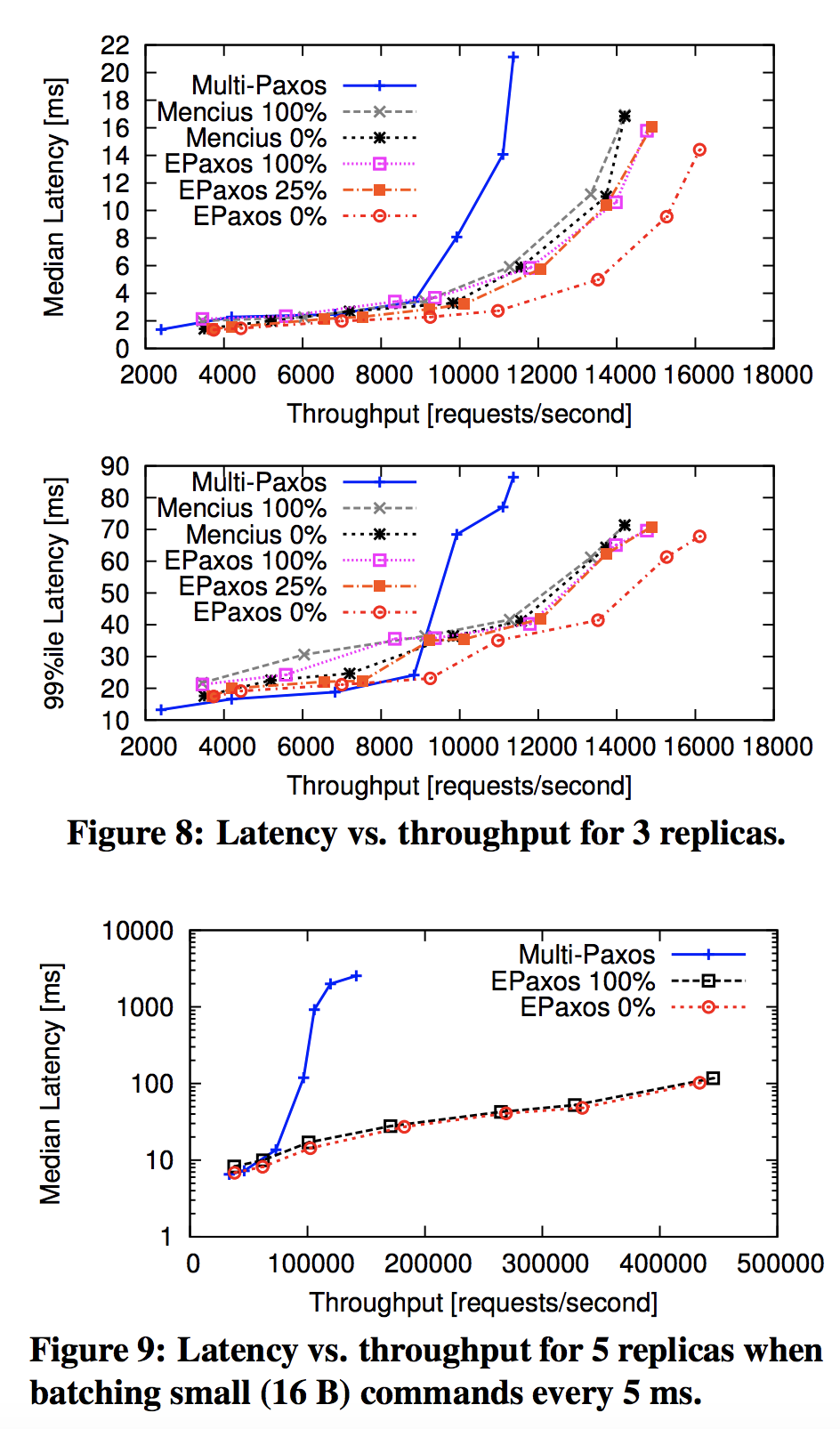

- Amazon EC2, using large instances for both state machine replicas and clients, running Ubuntu Linux 11.10.

- Quorum sizes: 3, 5

- Replicas located in Amazon EC2 datacenters in California (CA), Virginia (VA) and Ireland (EU), plus Oregon (OR) and Japan (JP) for the 5-replica experiment.

- 10 clients co-located w/ each replica (50 total). Clients generate requests simultaneously, and measure the commit and execute latency for each request.

- Latency is determined by a round-trip to the farthest replica.

Results

Latency

- 3 replicas w/ 100% interference: median execution latencies of 125-139 ms (depending on site).

- 5 replicas w/ 100% interference: median execution latencies of 304-319 ms (depending on site).

Throughput

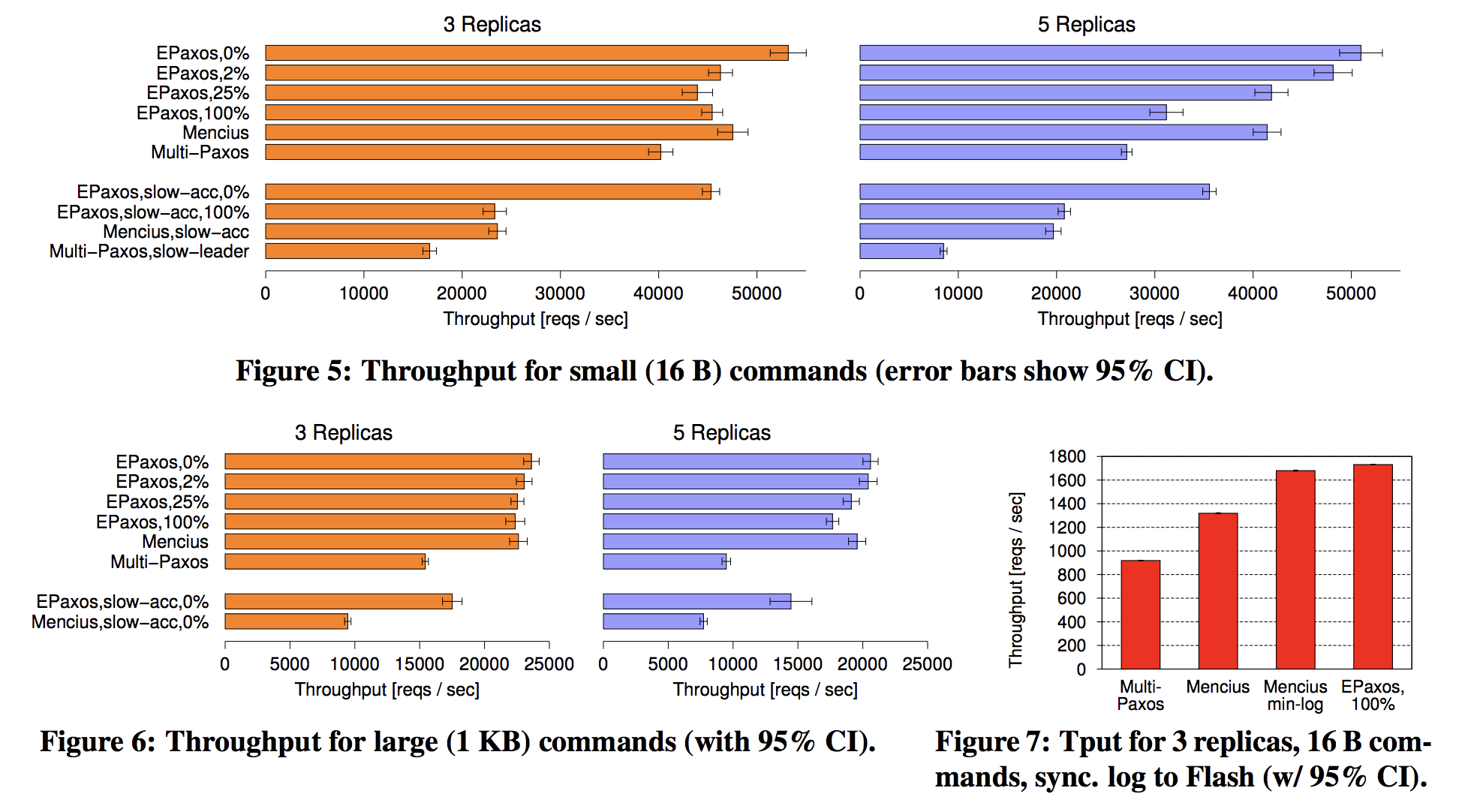

- 3 replica, 0% interference, 16 B commands: ~53,000 reqs/sec

- 3 replica, 2% interference, 16 B commands: ~46,250 reqs/sec

- 3 replica, 25% interference, 16 B commands: ~43,750 reqs/sec

- 3 replica, 100% interference, 16 B commands: ~45,250 reqs/sec

- 3 replica, slow-accept, 0% interference, 16 B commands: ~45,150 reqs/sec

- 3 replica, slow-accept, 100% interference, 16 B commands: ~23,750 reqs/sec

- 5 replica, 0% interference, 16 B commands: ~51,250 reqs/sec

- 5 replica, 2% interference, 16 B commands: ~48,125 reqs/sec

- 5 replica, 25% interference, 16 B commands: ~41,875 reqs/sec

- 5 replica, 100% interference, 16 B commands: ~31,250 reqs/sec

- 5 replica, slow-accept, 0% interference, 16 B commands: ~35,625 reqs/sec

- 5 replica, slow-accept, 100% interference, 16 B commands: ~21,000 reqs/sec

- 3 replica, 0% interference, 1 KB commands: ~23,250 reqs/sec

- 3 replica, 2% interference, 1 KB commands: ~22,750 reqs/sec

- 3 replica, 25% interference, 1 KB commands: ~22,500 reqs/sec

- 3 replica, 100% interference, 1 KB commands: ~22,250 reqs/sec

- 3 replica, slow-accept, 0% interference, 1 KB commands: ~17,500 reqs/sec

- 3 replica, slow-accept, 100% interference, 1 KB commands: ~9,000 reqs/sec

- 5 replica, 0% interference, 1 KB commands: ~20,500 reqs/sec

- 5 replica, 2% interference, 1 KB commands: ~20,250 reqs/sec

- 5 replica, 25% interference, 1 KB commands: ~18,750 reqs/sec

- 5 replica, 100% interference, 1 KB commands: ~19,500 reqs/sec

- 5 replica, slow-accept, 0% interference, 1 KB commands: ~14,250 reqs/sec

- 5 replica, slow-accept, 100% interference, 1 KB commands: ~7,500 reqs/sec

Notes For ePaxos, execution latency differs from commit latency because a replica must delay executing a command until it receives commit confirmations for the command’s dependencies.

Calvin

Alexander Thomson, Thaddeus Diamond, Shu-Chun Weng, Kun Ren, Philip Shao, and Daniel J Abadi. Calvin: Fast distributed transactions for partitioned database systems. In Proceedings of the 2012 ACM SIGMOD International Conference on Management of Data, pages 1–12. ACM, 2012

Abstract

Many distributed storage systems achieve high data access throughput via partitioning and replication, each system with its own advantages and tradeoffs. In order to achieve high scalability, however, today’s systems generally reduce transactional support, disallowing single transactions from spanning multiple partitions. Calvin is a practical transaction scheduling and data replication layer that uses a deterministic ordering guarantee to significantly reduce the normally prohibitive contention costs associated with distributed transactions. Unlike previous deterministic database system prototypes, Calvin supports disk-based storage, scales near-linearly on a cluster of commodity machines, and has no single point of failure. By replicating transaction inputs rather than effects, Calvin is also able to support multiple consistency levels — including Paxos-based strong consistency across geographically distant replicas — at no cost to transactional throughput.

Leadership Style

Strong leader. One replica is designated as master; transaction requests are forwarded to sequencers located at nodes of the master. After compiling each batch, the sequencer component on each master node forwards the batch to all other (slave) sequencers in its replication group. If the master fails, the replication group has to agree on (a) last valid batch and (b) specific transactions of that batch.

Experiments

- All experiments were run on Amazon EC2 using High-CPU/Extra-Large instances (7GB of memory and 20 EC2 Compute Units — 8 virtual cores w/ 2.5 EC2 Compute Units each)

- 4 EC2 High-CPU machines per replica, running 40000 microbenchmark transactions per second (10000 per node), 10% of which were multipartition

- Quorum size: 3 (12 total nodes)

- Across data centers, one replica on Amazon’s East US (Virginia) data center, one on Amazon’s West US (Northern California) data center, and one on Amazon’s EU (Ireland) data center. Ping times between replicas ranged from 100-170 ms. 1ms ping time between replicas within a single data center.

- 2 benchmarks: TPC-C and custom microbenchmark.

Results

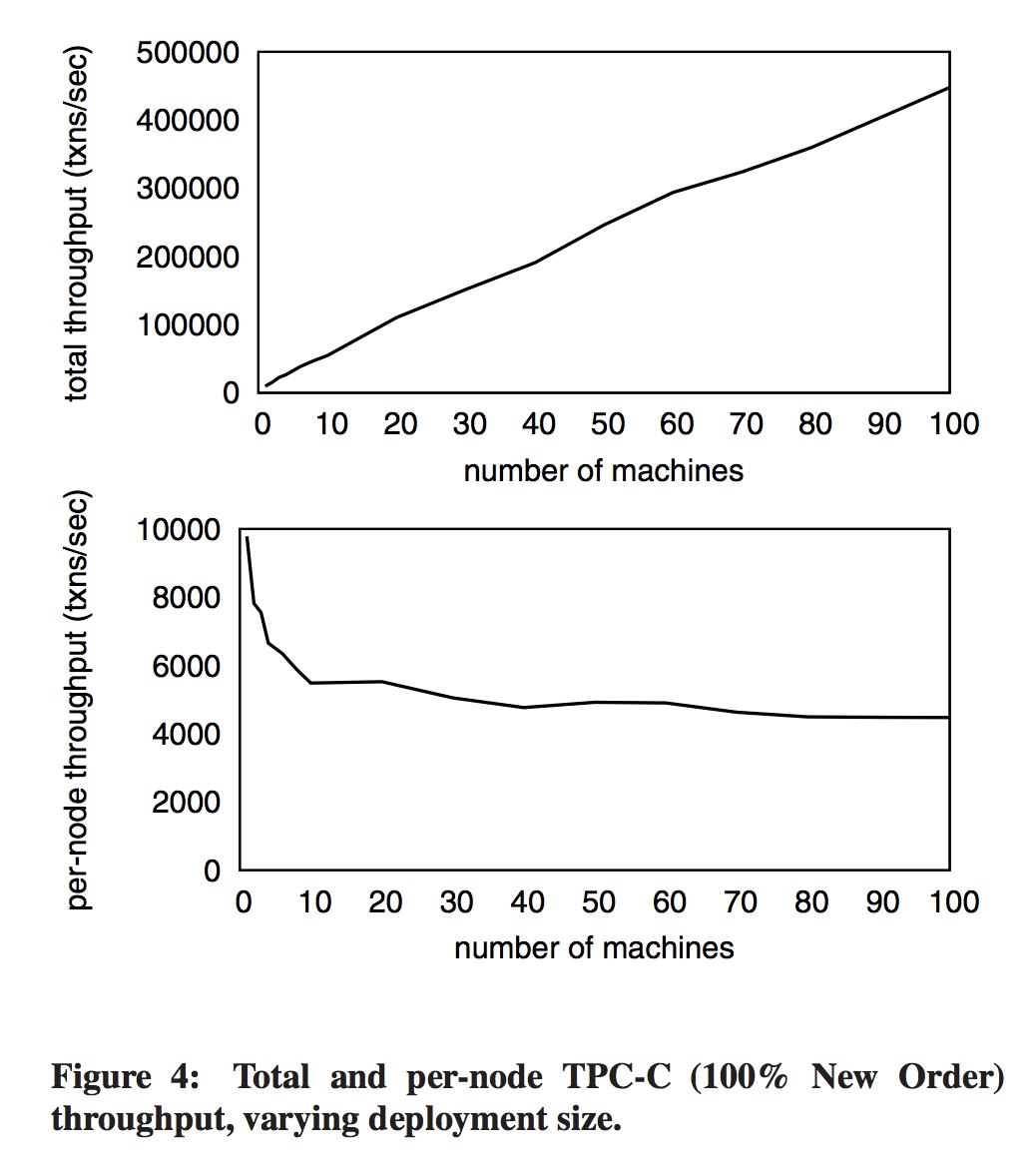

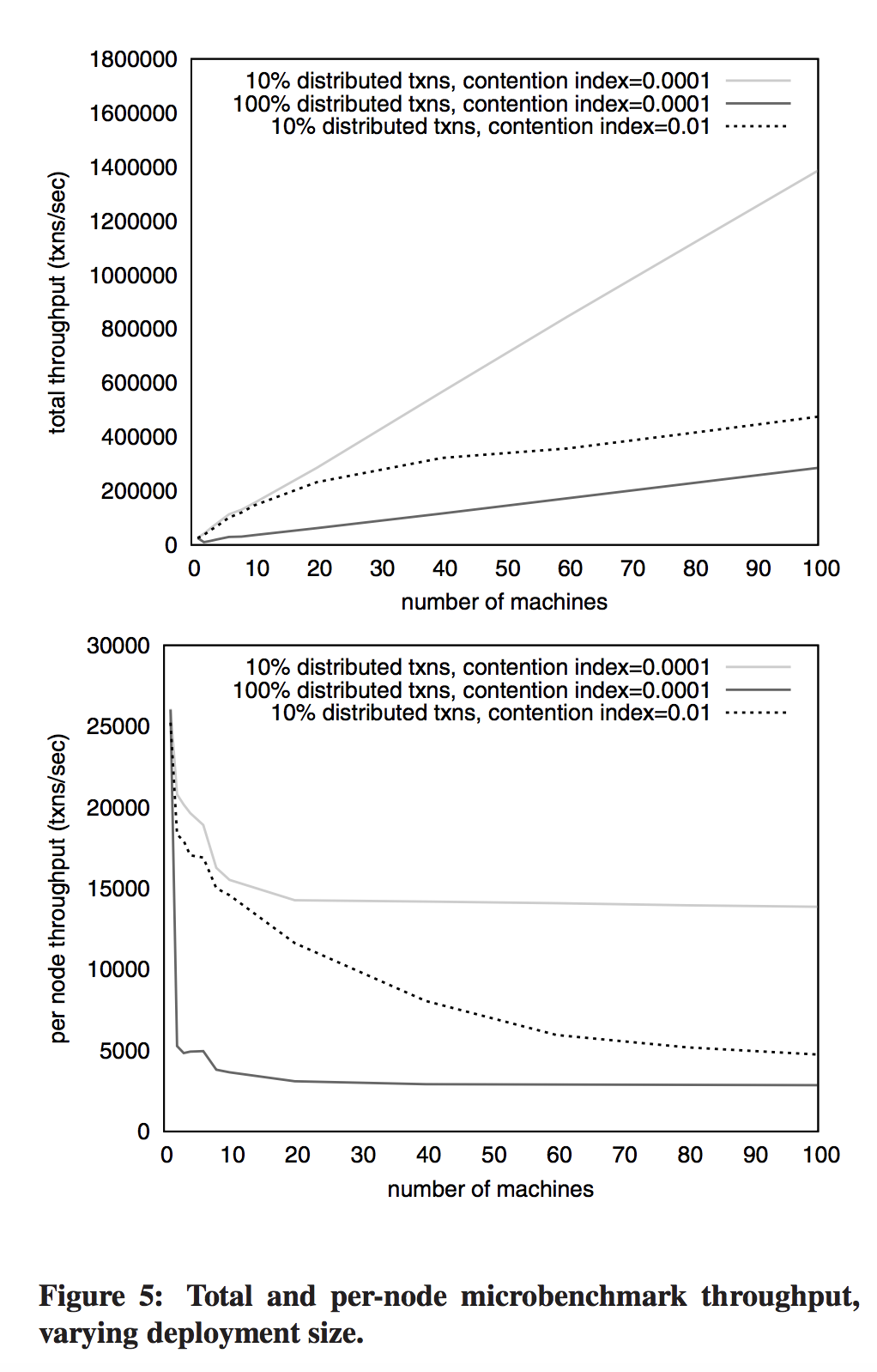

- Without agreement protocol, ~5,000 transactions per second per node in clusters larger than 10 nodes, and scales linearly.

- Can achieve nearly half a million TPC-C transactions per second on a 100 node cluster.

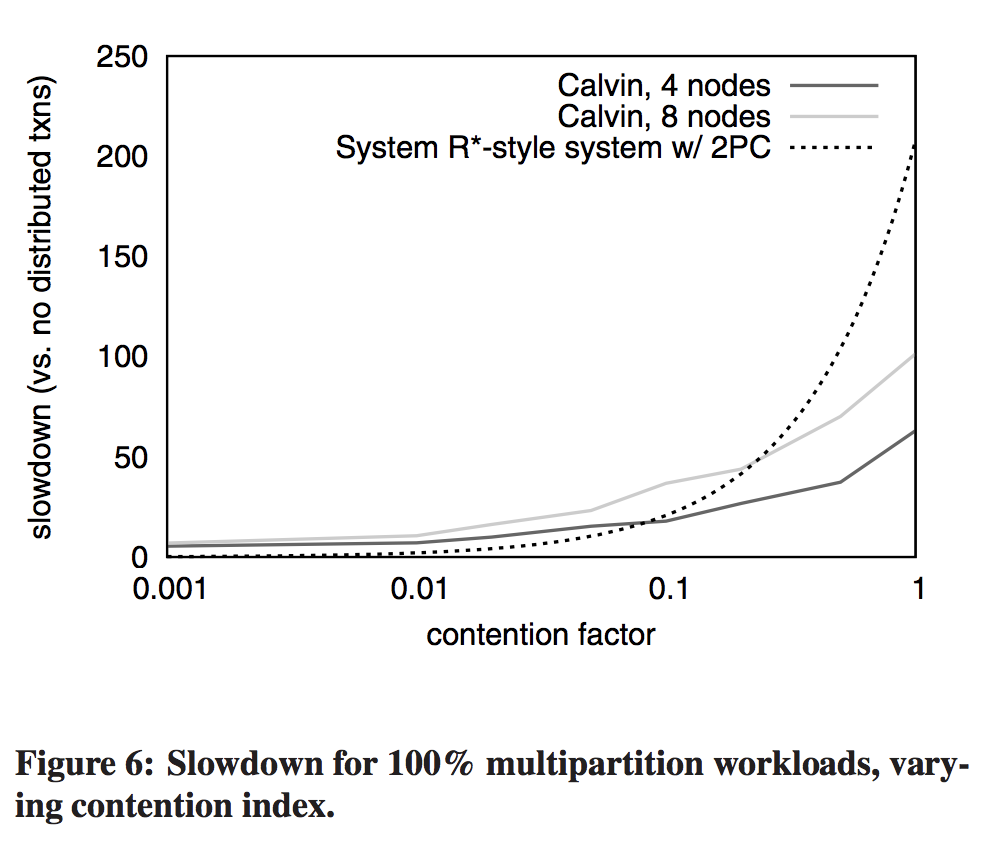

- Under low contention, 5x to 7x slowdown — from 27,000 transactions per second to about 5,000 transactions per second (4 nodes) or 4,000 transactions per second (8 nodes). Same slowdown as seen going from 1 machine to 4 or 8.

Notes

The more machines there are, the more likely at any given time there will be at least one that is slightly behind for some reason. The fewer machines there are in the cluster, the more each additional machine will increase skew. The higher the contention rate, the more likely a machine’s random slowdown will slow others. Not all EC2 instances yield equivalent performance, and sometimes an EC2 user gets stuck with a slow instance — a slightly slow machine was added when they went from 6 nodes to 8 nodes.

MDCC

Tim Kraska, Gene Pang, Michael J. Franklin, Samuel Madden, and Alan Fekete. MDCC: Multi-Data Center Consistency. In Proceedings of the 8th ACM European Conference on Computer Systems, pages 113–126. ACM, 2013.

Abstract

Replicating data across multiple data centers allows using data closer to the client, reducing latency for applications, and increases the availability in the event of a data center failure. MDCC (Multi-Data Center Consistency) is an optimistic commit protocol for geo-replicated transactions, that does not require a master or static partitioning, and is strongly consistent at a cost similar to eventually consistent protocols. MDCC takes advantage of Generalized Paxos for transaction processing and exploits commutative updates with value constraints in a quorum-based system. Our experiments show that MDCC outperforms existing synchronous transactional replication protocols, such as Megastore, by requiring only a single message round-trip in the normal operational case independent of the master-location and by scaling linearly with the number of machines as long as transaction conflict rates permit.

Leadership Style

No strong leader required. Needs only a single wide-area message round-trip to commit a transaction in the common case. Is “master-bypassing” — can read or update from any node in any data center.

Experiments

- Amazon EC2: US West (N. California), US East (Virginia), EU (Ireland), Asia Pacific (Singapore), and Asia Pacific (Tokyo).

- m1.large instances (4 cores, 7.5GB memory)

- 2 benchmarks: TPC-W (e-commerce transactions) and micro-benchmark

- TPC-W scale factor of 10,000 items, w/ data evenly partitioned and replicated to 4 storage nodes per data center. 100 evenly geo-distributed clients (on separate machines) each ran the TPC-W benchmark for 2 minutes, after a 1 minute warm-up period.

- compared MDCC to other transactional and other non-transactional, eventually consistent protocols.

- Quorum size:

- Write quorum: 3/5 replicas (“QW-3”) and 4/5 replicas (“QW-4”)

- Read quorum: 1/5 replicas

- scale-out experiment: 50 clients w/ 5,000 items => 100 clients w/ 10,000 items => 200 clients w/ 20,000 items (fixed amount of data per storage node to a TPC-W scale-factor of 2,500 items; scaled the number of nodes accordingly)

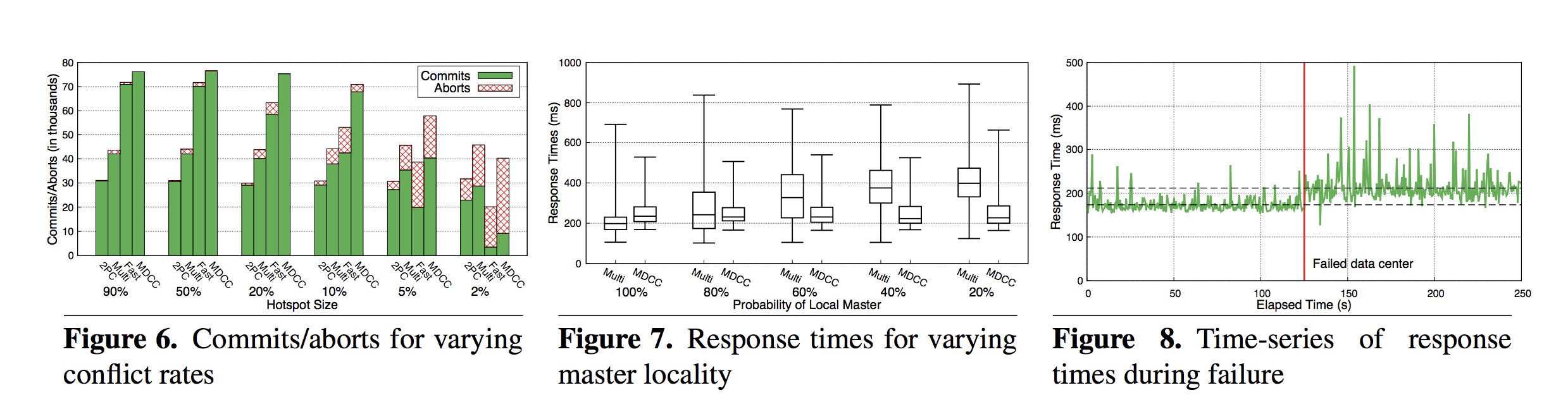

Results

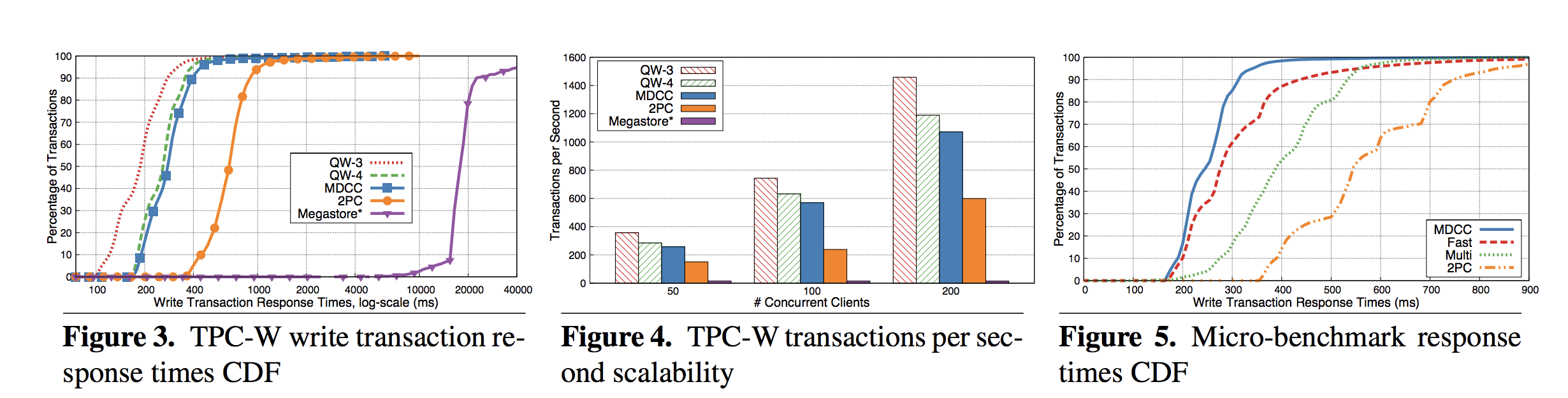

Median response times for TPC-W

- 188ms for QW-3 (non-transactional)

- 260ms for QW-4 (non-transactional)

- 278ms for MDCC (transactional)

- 668ms for 2-phase commit (transactional)

- 17,810ms for Megastore (transactional)

Throughput

- 50 concurrent clients: ~250 txns per sec

- 100 concurrent clients: ~575 txns per sec

- 200 concurrent clients: ~1075 txns per sec (within 10% of throughput of QW-4)

- MDCC has higher throughput than 2-phase commit and Megastore.

- QW protocols scale almost linearly; similar scaling for MDCC and 2PC.

Median response times for micro-benchmark

- 245ms for MDCC (full protocol)

- 276ms for Fast (without commutative update support)

- 388ms for Multi (all instances Multi-Paxos so a stable master can skip Phase 1)

- 543ms for 2-phase commit

Failure Scenario

- 173.5 ms avg response time before data center failure

- 211.7 ms avg response time after data center failure

Boxwood

John MacCormick, Nick Murphy, Marc Najork, Chandramohan A. Thekkath, and Lidong Zhou. Boxwood: Abstractions as the Foundation for Storage Infrastructure. In OSDI, volume 4, pages 105–120, 2004.

Abstract

Writers of complex storage applications such as distributed file systems and databases are faced with the challenges of building complex abstractions over simple storage devices like disks. These challenges are exacerbated due to the additional requirements for fault tolerance and scaling. This paper explores the premise that high-level, fault-tolerant abstractions supported directly by the storage infrastructure can ameliorate these problems. We have built a system called Boxwood to explore the feasibility and utility of providing high-level abstractions or data structures as the fundamental storage infrastructure. Boxwood currently runs on a small cluster of eight machines. The Boxwood abstractions perform very close to the limits imposed by the processor, disk, and the native networking subsystem. Using these abstractions directly, we have implemented an NFSv2 file service that demonstrates the promise of our approach.

Leadership Style

Uses a single master. Lock service w/ single master server and 1+ slave servers. Only master hands out leases. Master’s identity is part of the global state. Lock service keeps the list of clerks as state. If master dies, slave takes over after passing a Paxos decree that changes the identity of the current master. New master recovers lease state by reading Paxos state to get list of clerks & gets lease state from them.

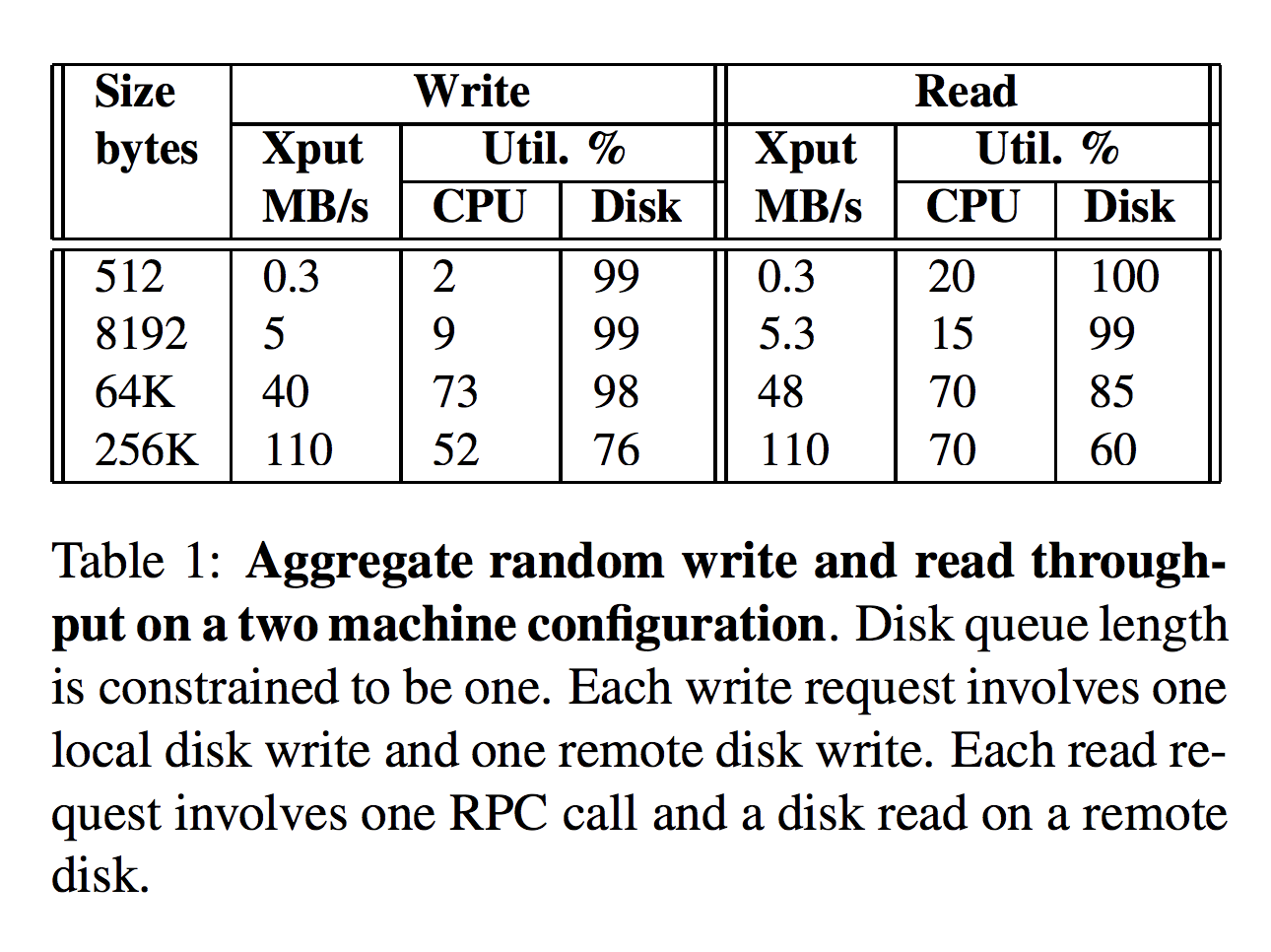

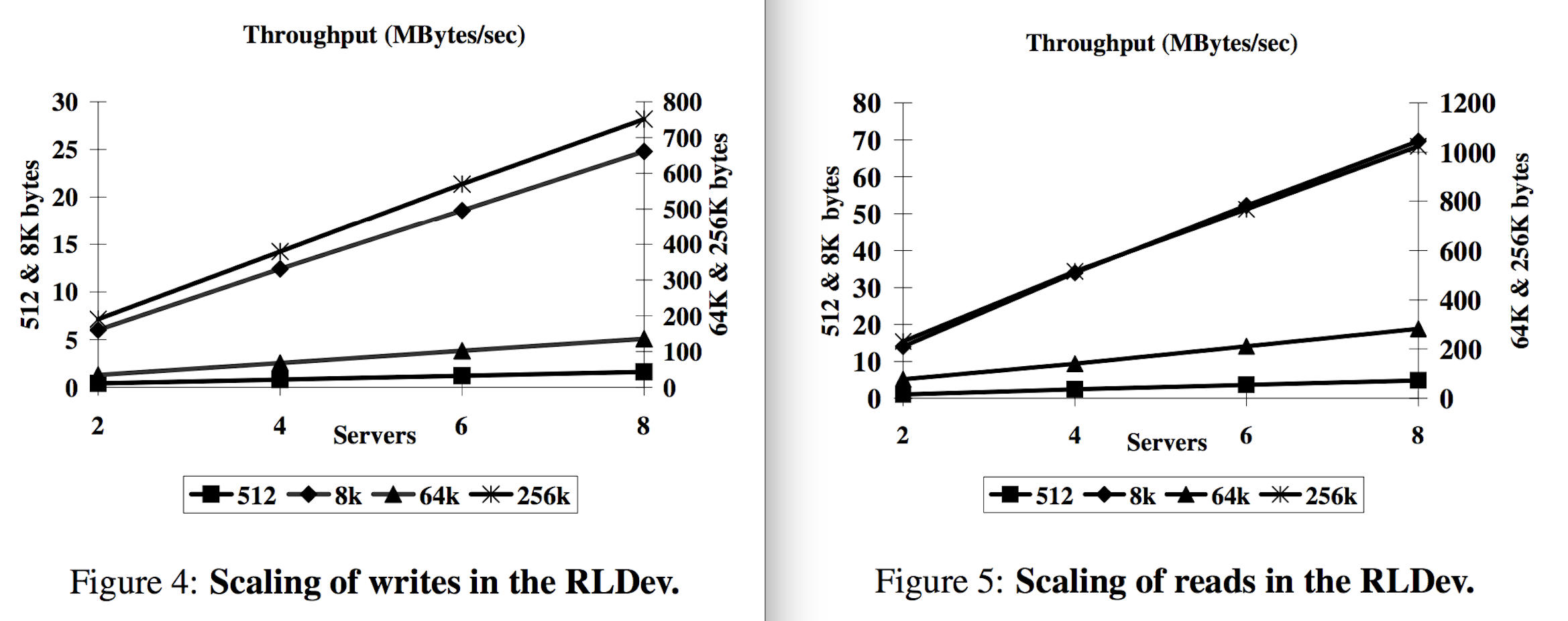

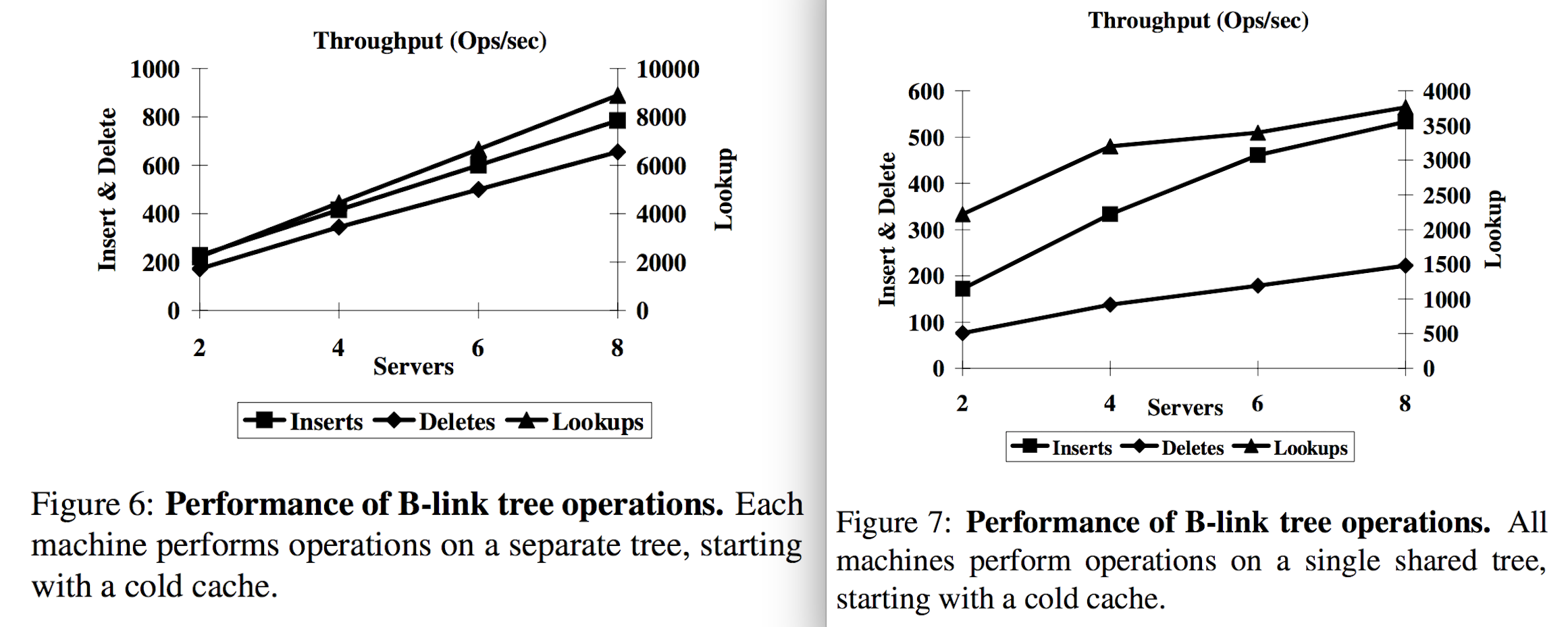

Experiments

- Deployed on cluster of eight machines connected by a Gigabit Ethernet switch. Each machine is a Dell PowerEdge 2650 server with a single 2.4 GHz Xeon processor, 1GB of RAM, with an Adaptec AIC-7899 dual SCSI adapter, and 5 SCSI drives. One of these, a 36GB 15K RPM (Maxtor Atlas15K) drive, is used as the system disk. The remaining four 18GB 15K RPM drives (Seagate Cheetah 15K.3 ST318453LC) store data.

- Boxwood runs as a user-level process on a Windows Server 2003 kernel.

- Networking subsystem can transmit data at 115 MB/sec using TCP. RPC system can deliver ~110 MB/sec.

Results

Throughput

Latency

(Effect of batching on allocations)

- batch size 1: 24 ms

- batch size 10: 3.3 ms

- batch size 100: 1.0 ms

- batch size 1000: 1.0 ms

B-Tree

Niobe

John MacCormick, Chandramohan A. Thekkath, Marcus Jager, Kristof Roomp, Lidong Zhou, and Ryan Peterson. Niobe: A practical replication protocol. 3(4):1, 2008.

Abstract

The task of consistently and reliably replicating data is fundamental in distributed systems, and numerous existing protocols are able to achieve such replication efficiently. When called on to build a large-scale enterprise storage system with built-in replication, we were therefore surprised to discover that no existing protocols met our requirements. As a result, we designed and deployed a new replication protocol called Niobe. Niobe is in the primary-backup family of protocols, and shares many similarities with other protocols in this family. But we believe Niobe is significantly more practical for large-scale enterprise storage than previously-published protocols. In particular, Niobe is simple, flexible, has rigorously-proven yet simply-stated consistency guarantees, and exhibits excellent performance. Niobe has been deployed as the backend for a commercial Internet service; its consistency properties have been proved formally from first principles, and further verified using the TLA+ specification language. We describe the protocol itself, the system built to deploy it, and some of our experiences in doing so.

Leadership Style

Uses the “primary-backup” or “primary copy” paradigm for fault-tolerance — primary receives an update from client, sends it to one or more secondaries, and then replies to client. Some machines (less than 10) run a global state manager (GSM) module, which uses a consensus service (Paxos) to reliably store critical global state used by storage and policy manager subsystems. Technique of using the GSM to kill and reincarnate secondaries, while using all live replicas (but not the GSM) for performing updates, is mathematically equivalent to the “wheel” quorum system.

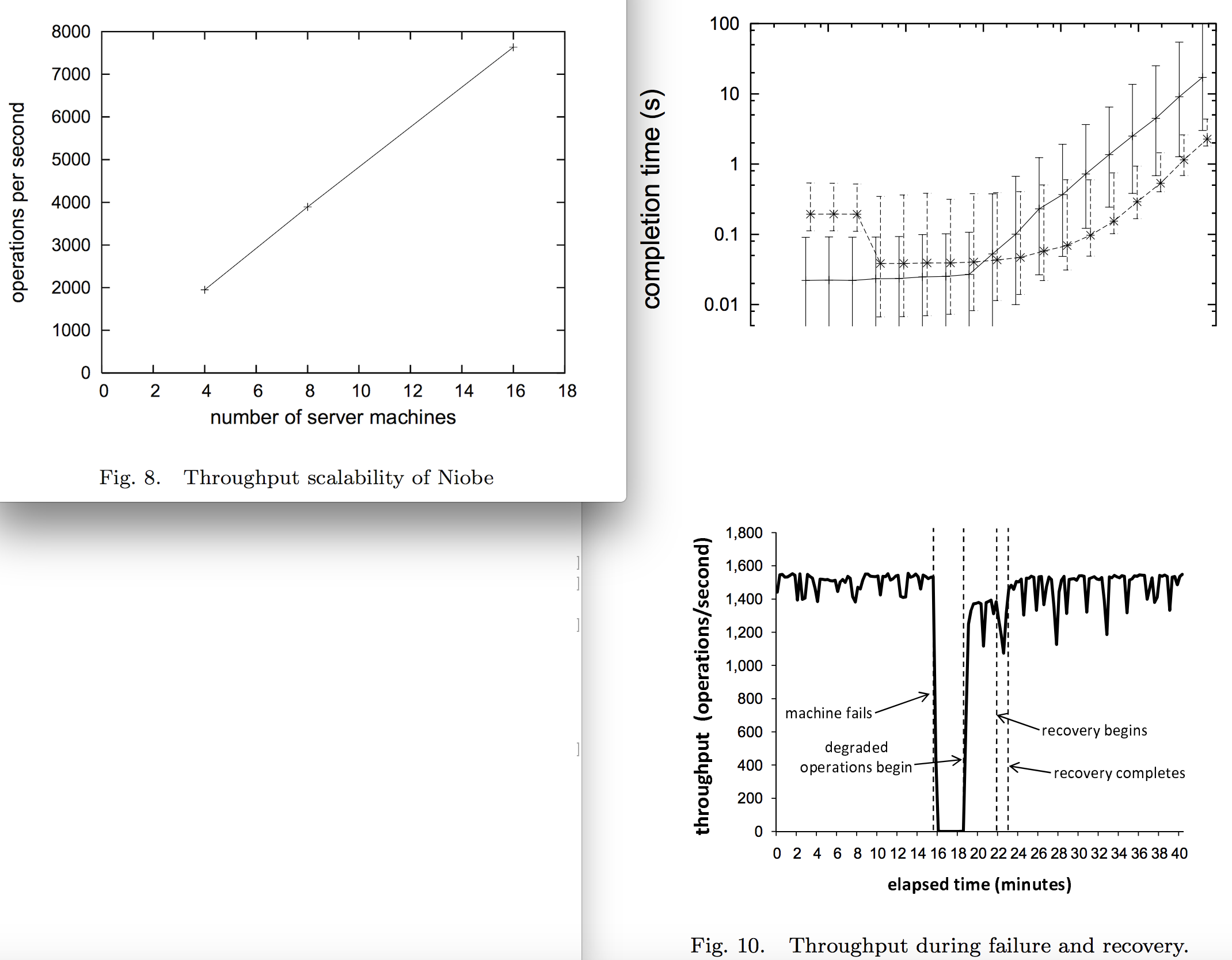

Experiments & Results

Note: these aren’t framed exactly as experiments & results so much as observations of the deployed system

- Typical server-class rack-mounted machines, connected by a combination of 100 Mb and Gigabit ethernet in a data center. Each machine has multiple processors, a “modest amount” of memory, several terabytes of attached storage in one or two disk arrays.

- 2 hardware configurations: RAID-5 and JBOD

- Quorum size: N = 2, 3, “or more”

Mencius

Yanhua Mao, Flavio Paiva Junqueira, and Keith Marzullo. Mencius: Building efficient replicated state machines for WANs. In OSDI, volume 8, pages 369–384, 2008.

Abstract

We present a protocol for general state machine replication – a method that provides strong consistency – that has high performance in a wide-area network. In particular, our protocol Mencius has high throughput under high client load and low latency under low client load even under changing wide-area network environment and client load. We develop our protocol as a derivation from the well-known protocol Paxos. Such a development can be changed or further refined to take advantage of specific network or application requirements.

Leadership Style

Implements a multi-leader state machine replication protocol derived from Paxos.

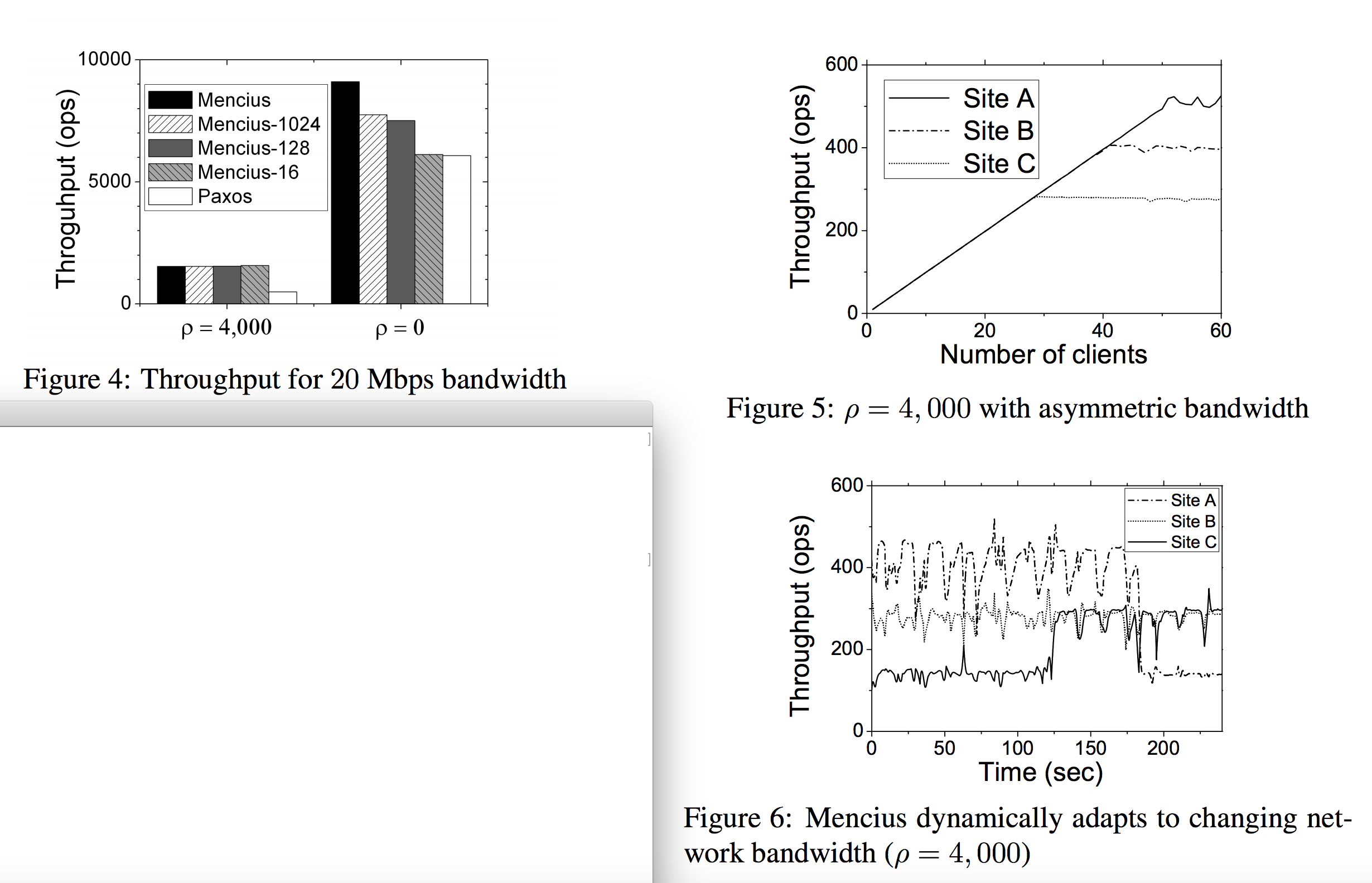

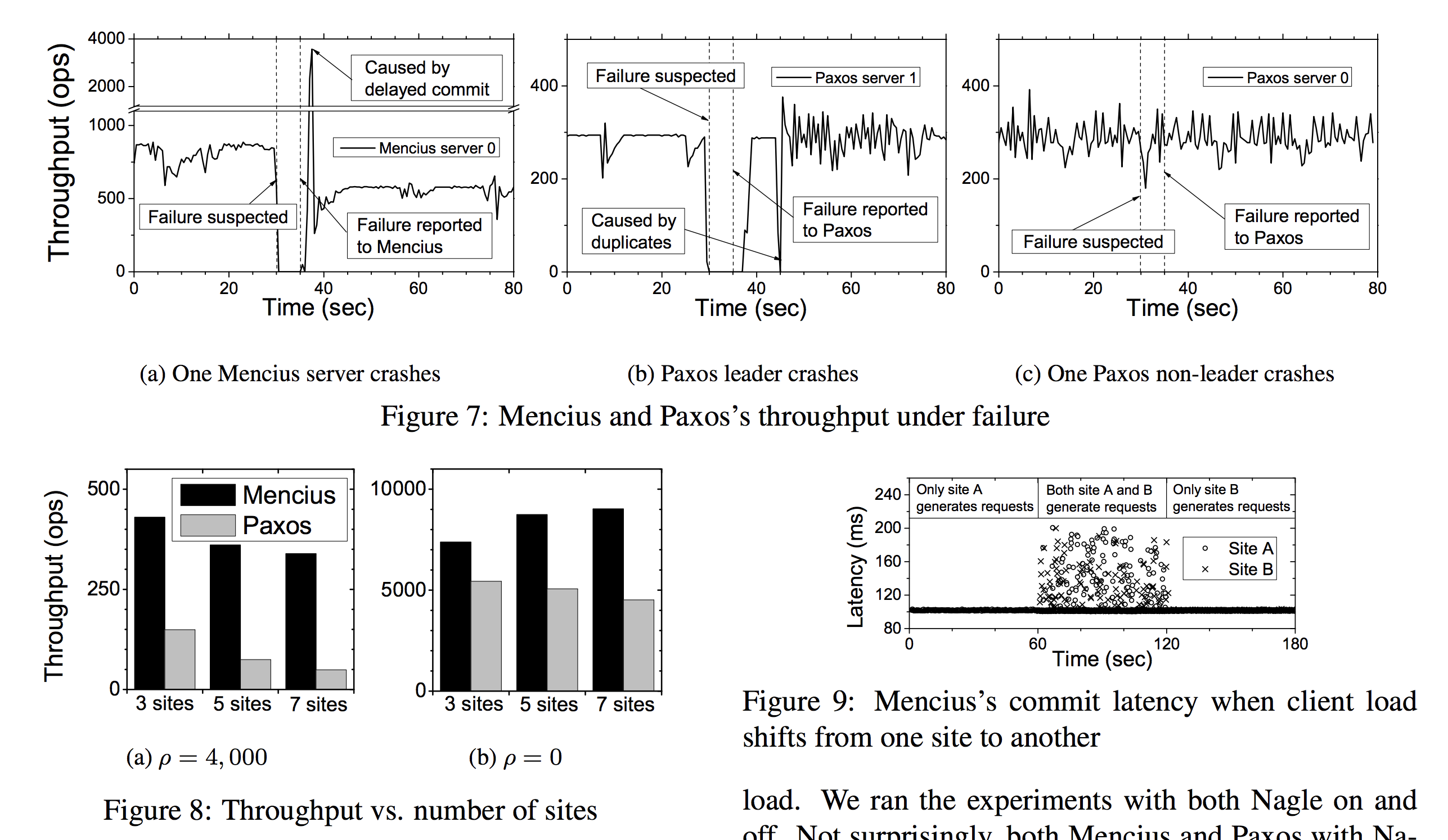

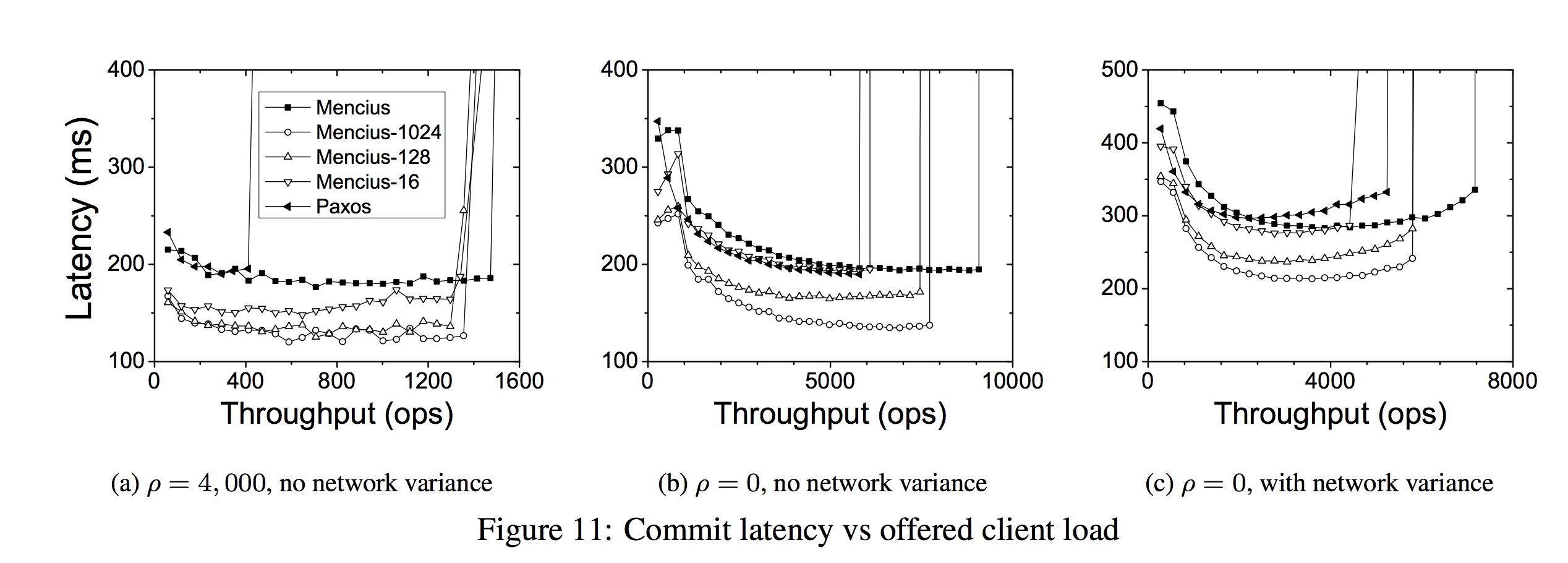

Experiments

- parameters: 20 messages, 50 ms, 100,000 instances.

- 3-server clique simulating 3 data centers (A, B and C) connected by dedicated links. Each site had one server node running the replicated register service, and one client node that generated all the client requests from that site. Each node was a 3.0 GHz Dual-Xeon PC with 2.0 GB memory running Fedora 6.

- Each client generated requests at either a fixed rate or with inter-request delays chosen randomly from a uniform distribution. 0 or 4,000 byte payload, w 5/ 50% read requests and 50% write requests. Each client generated requests at a constant rate of 100 ops.

Results

- When

ρ = 4,000, the system was network-bound: all four Mencius variants had a fixed throughput of about 1,550 operations per sec (ops). This corresponds to 99.2 Mbps, or 82.7% utilization of the total bandwidth, not counting the TCP/IP and MAC header overhead. Paxos had a throughput of about 540 ops, or one third of Mencius’s throughput. - When

ρ = 0, the system is CPU-bound. Paxos presents a throughput of 6,000 ops, with 100% CPU utilization at the leader and 50% at the other servers. - Site C eventually saturated its outgoing links first; and from that point on committed requests at a maximum throughput of 285 ops. Throughput at both A and B increased until site B saturated its outgoing links at 420 ops. Finally site A saturated its outgoing links at 530 ops. Maximum throughput at each site is proportional to the outgoing bandwidth.

- Site A, B and C initially committed requests with throughput of about 450 ops, 300 ops, and 150 ops respectively, reflecting the bandwidth available to them.

Corfu

Mahesh Balakrishnan, Dahlia Malkhi, Vijayan Prabhakaran, Ted Wobber, Michael Wei, and John D Davis. CORFU: A Shared Log Design for Flash Clusters. In NSDI, pages 1–14, 2012.

Abstract

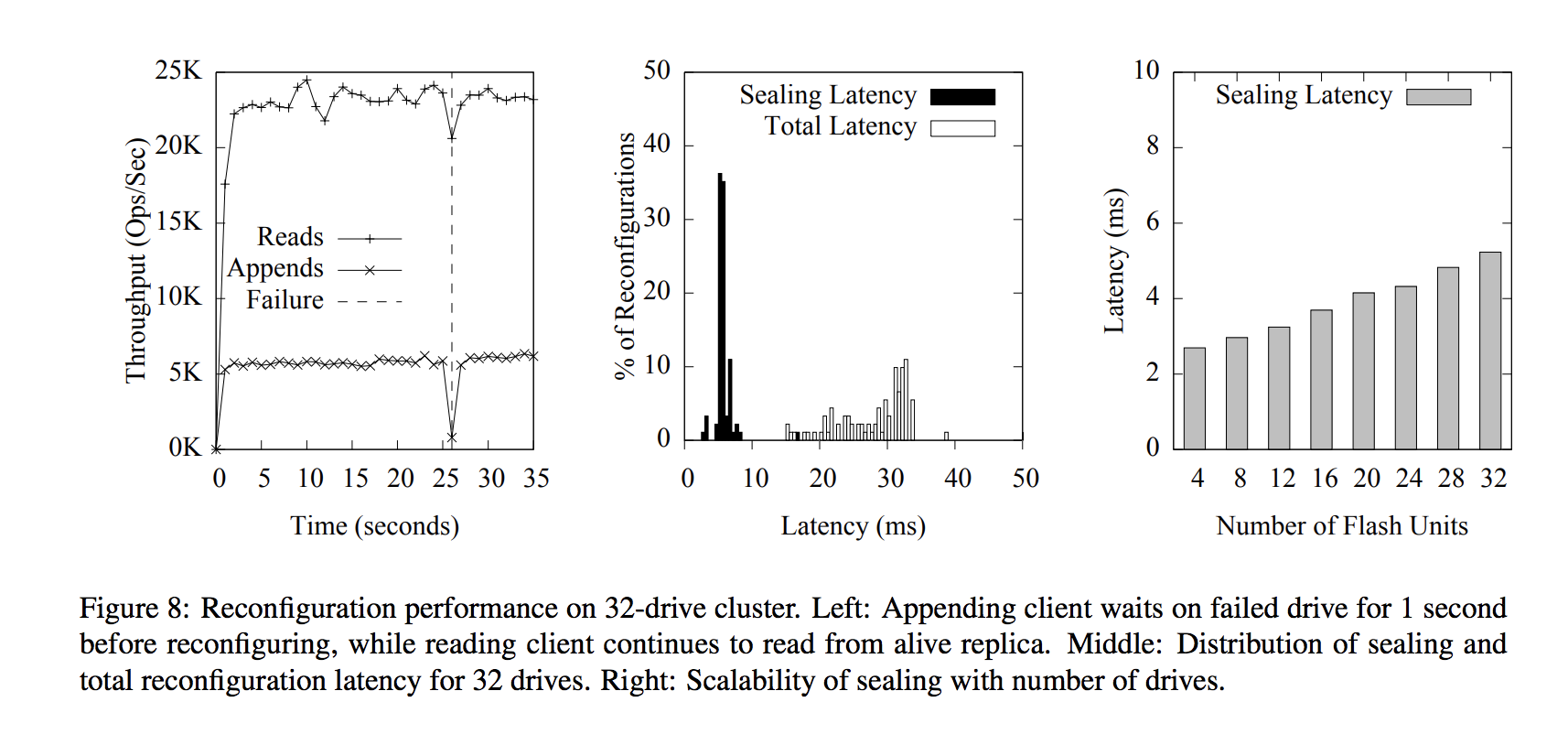

CORFU organizes a cluster of flash devices as a single, shared log that can be accessed concurrently by multiple clients over the network. The CORFU shared log makes it easy to build distributed applications that require strong consistency at high speeds, such as databases, transactional key-value stores, replicated state machines, and metadata services. CORFU can be viewed as a distributed SSD, providing advantages over conventional SSDs such as distributed wear-leveling, network locality, fault tolerance, incremental scalability and geodistribution. A single CORFU instance can support up to 200K appends/sec, while reads scale linearly with cluster size. Importantly, CORFU is designed to work directly over network-attached flash devices, slashing cost, power consumption and latency by eliminating storage servers.

Leadership Style

Chain replication

When a client wants to write to a replica set of flash pages, it updates them in a deterministic order, waiting for each flash unit to respond before moving to the next one. The write is successfully completed when the last flash unit in the chain is updated. As a result, if two clients attempt to concurrently update the same replica set of flash pages, one of them will arrive second at the first unit of the chain and receive an error overwrite. This ensures safety-under-contention.

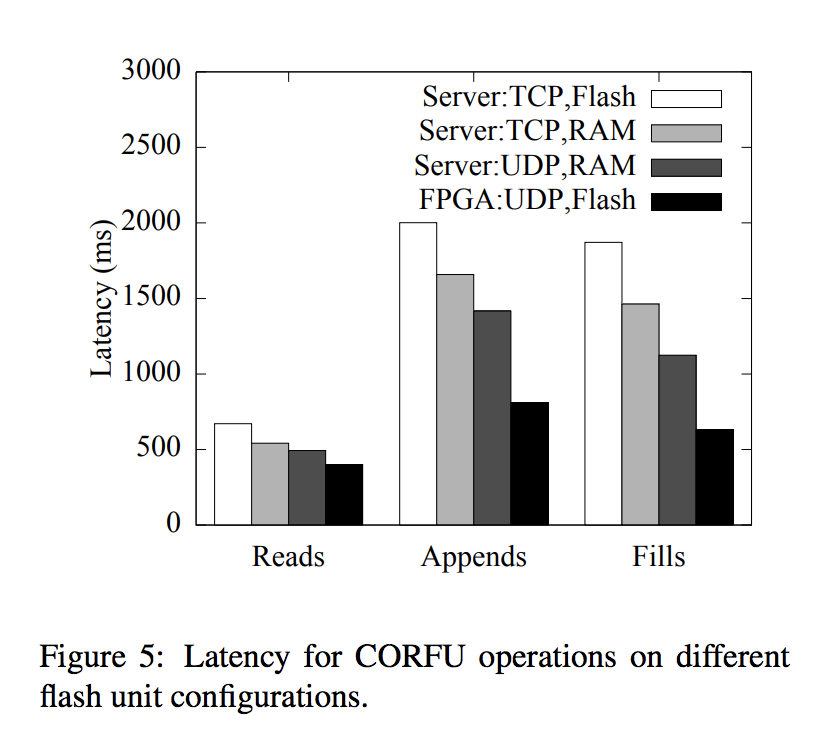

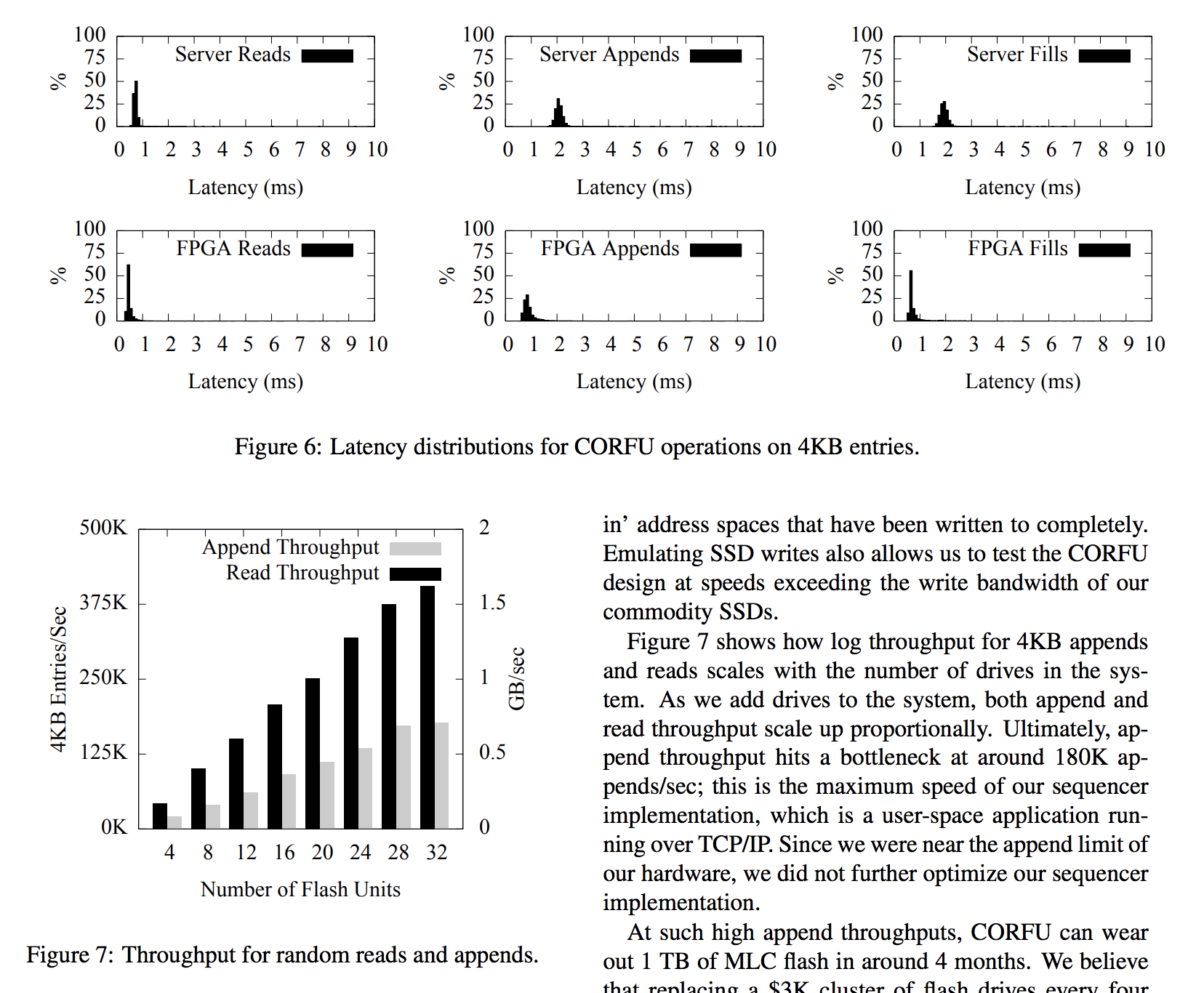

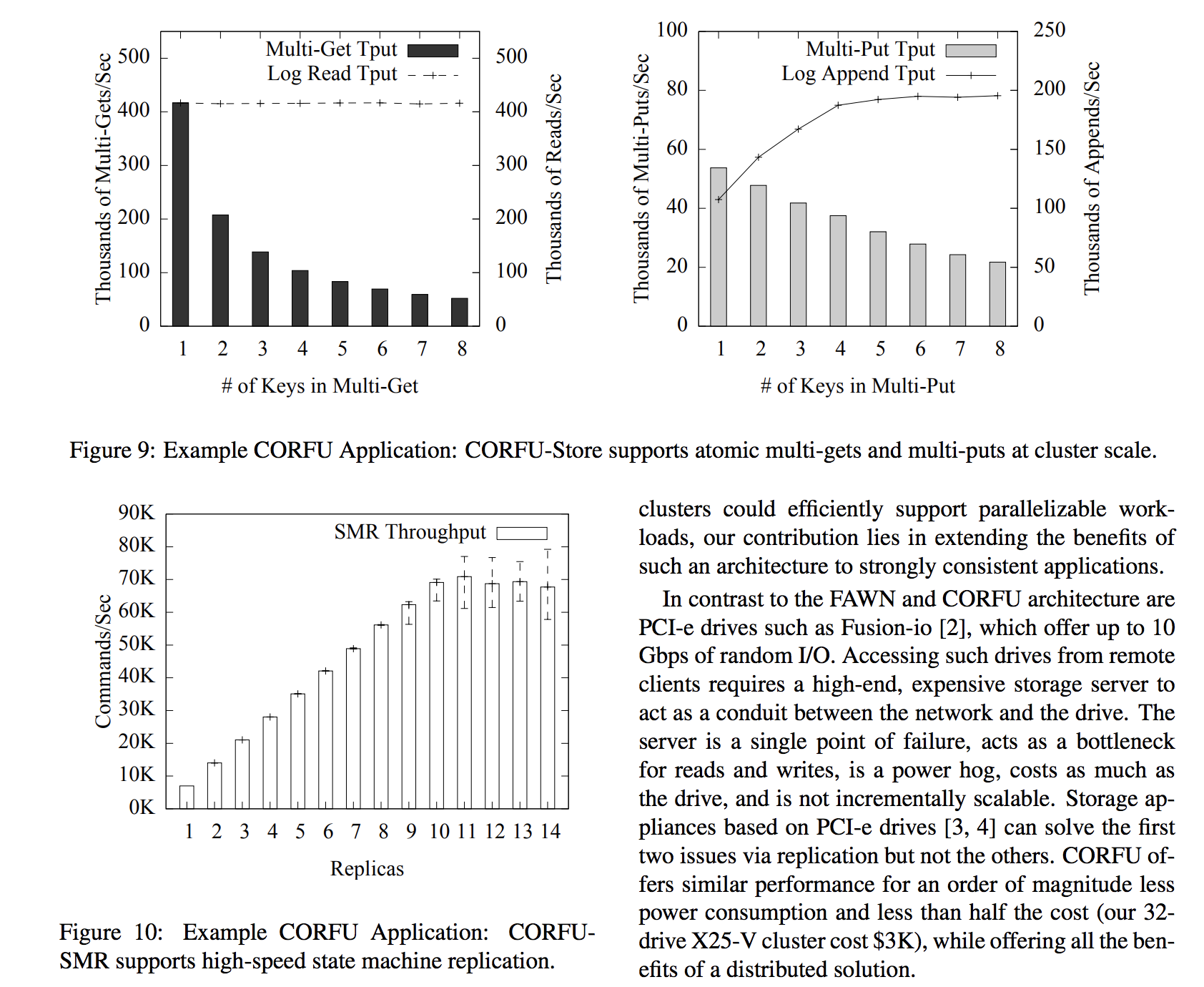

Results

Latency